|

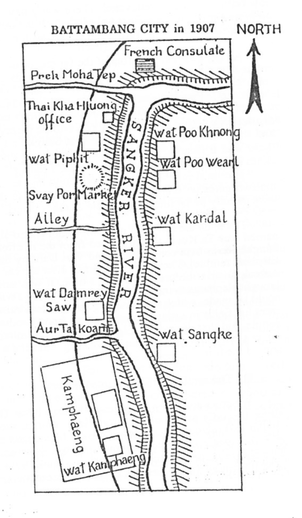

Update September 1st, 2020: as the investigation into the fire reveals more information, it seems the market is salvageable. 33 stalls were destroyed and another 44 were damaged (of the over 700 inside the building). The fire is believed to have been caused by bad electrical wiring (which is anything but surprising given the way wires work in Cambodia), and a structural assessment of the building is ongoing. The fire was largely contained to the western half, meaning that the clock tower in the eastern portion got a little dirty from smoke but seems to be standing just fine. I have heard many local friends claim that the fire may end up being a good thing, as plans are already underway to clean and paint the market to make it look even better than it did before. I am much relieved to know that the damage is not as severe as initially thought, even if some of my post is made irrelevant by that information. For the sake of posterity, and because these issues are still important to consider at the market and beyond, I am leaving this post up in its original format. Soon after 6pm on Sunday, August 30th, 2020, hundreds of Cambodians encircled Psaa Nat - the Meeting Market - and watched helplessly as flames engulfed the structure’s empty clock tower that points just ever-so-slightly southeast towards the Sangkae River. For nearly 90 years, Psaa Nat stood as one of the most iconic buildings in the northwestern Cambodian city of Battambang - visible on tourist t-shirts and postcards, and often serving as a backdrop for photos for locals and visitors alike. The cause of the fire is as-yet unknown, although there were storms in the area so lightning is a possibility, as is the spread of an open fire through the textile market from a range of sources. Unable to visit Battambang myself this summer due to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, I sat on my couch in Green Bay, Wisconsin watching in horror as my research assistant Visal sent me live photos and videos of the conflagration. Like so many residents of Battambang, I have a deeply personal connection with Psaa Nat. On my first trip to Battambang in 2009, I stayed the first night of my lifetime fascination with the city in the Royal Hotel directly adjacent to Psaa Nat’s western entrance. One of my best friends in Battambang sold clothing in the market, and I even had jewelry made there for my family on my last visit (in addition to one of my own Buddha amulets). I’ve spent countless hours sitting amongst the piles of shoes and textiles talking to vendors and shoppers about their lives, and one of my favorite picture spots in the region is directly across the river to the east facing towards Psaa Nat’s skeletal clock tower. While my grief is but a fraction of that felt by those who depended on the market for their livelihoods, I know that everyone who loves Battambang for its unique magic is heartbroken to see the images of this beloved building swallowed by unforgiving flames. The good news is that, as of this writing, there are no reported deaths caused by the fire. The bad news is that, in a summer already occupied with a seemingly unending barrage of problems, local officials estimate that the building is 80% lost and is unlikely to be saved (although damage may be largely contained in the western half without the clock tower). Not only will the loss of the market directly affect the hundreds of people directly dependent on Psaa Nat for their income, but the building’s loss creates several obstacles for urban development and the problematic politics that often occur in Cambodia. First, Battambang City is in the midst of applying for UNESCO World Heritage Status - a politically motivated designation that carries with it the potential for significant gains in tourism(both domestic and international) and urban development. Battambang markets itself as the “Charming City” - a title invented to emphasize the city’s timeless feel and highlight the hundreds of French colonial (and pre-French colonial) buildings for which the city is known. Psaa Nat was one of the most instantly recognizable of these buildings - an emblem of Battambang as a “pocket of the past,” to quote a 2011 feature piece about the city in The New York Times. The now-burned structure was designed and constructed in 1936-1937 by Jean Desbois and Louis Chauchon, who were also responsible for Cambodia’s most famous market - the contemporaneous Psaa Thmei (New Market) in Phnom Penh. The market was built in two halves, with the larger western half containing most of the stalls and the smaller eastern half containing enclosed shop space at the end, adorned by an art deco clocktower. The walkway separating the two parts became an open-air food market, and one of the best places in town to sit, eat some authentic Khmer cuisine, and watch people go about their business. During the violent Khmer Rouge regime in the late 1970s, most of the market’s adornments were removed, leaving behind bare concrete walls and the cut-outs that once housed the clock mechanism. The resulting tower thus became a photogenic symbol of local history ranging from colonial occupation to genocidal conflict to recent recovery. While most people assume the French built the market, it’s important to note that the French are actually only responsible for the market building itself. Before the French took control of the region in 1907, Battambang was ruled as a quasi-independent tributary state by the Aphaiwong dynasty, who were Khmer born but loyal to the Thai monarchy. Maps from this period indicate that the land upon which the French built Psaa Nat was designated a market space far before French arrival, and thus it may be said that the Khmer (with Thai influence) organized Battambang’s downtown heritage district in whilst the French merely built up those foundations into what most people recognize today. Nevertheless, the complicated historical narrative represented by Psaa Nat is precisely what appeals to organizations like UNESCO and could transform Battambang into an internationally-known heritage city. While many other buildings still exist from that time period, the loss of Psaa Nat will certainly force the city to revise its UNESCO strategy. In so doing, a new danger arises: the blight of corruption in Cambodian urban development. Gut reaction tells me that most residents of Battambang will want to rebuild Psaa Nat, assuming most of it cannot be saved. As an icon of their city, of which I have always known them to be extremely proud, Psaa Nat carries deep meaning for locals and they will not let it go easily. Furthermore, Cambodians care deeply about architectural heritage, inspired in part by the importance of Angkor Wat in nationalistic iconography. When the cathedral of Notre-Dame burned in Paris in April 2019, most Cambodians I knew openly mourned the loss of such a great religious structure - even if (and perhaps partly because) it represented a foreign religion from a country that once imposed itself on them. Most of my Cambodian friends changed their social media profile photos and retweeted hashtags to empathize with the French. No one is likely to do the same for the people of Battambang, but locals will mourn their loss in much the same way that the world mourned for Paris. Unfortunately, even if the people of Battambang want to rebuild the market, it is not a guarantee. Psaa Nat occupies prime real estate in the direct heart of Battambang’s heritage district. A large plot of land near the river and other important government buildings, the temptation to sell the land for a profit will loom large over local government. In recent years, Cambodian officials have been heavily criticized for selling off land (occupied or not) to foreign investors, and for tearing down important buildings (such as the White Building in Phnom Penh) for dubious reasons - with bribery and kickbacks being obvious but never explicitly stated reasons. Battambang is no stranger to this behavior, as a Gloria Jean’s Coffee took over one of the most picturesque former colonial buildings along the waterfront in 2016, with a KFC soon following nearby, despite local protests. Standing kitty-corner to Psaa Nat’s western entrance, the Green Tower - so called because of the green construction tarps draped over it - has stood empty for nearly a decade, having been poised to become the city’s tallest building (again, despite local protest) but abandoned due to financial collapse before the walls were finished. Numerous investors will undoubtedly turn a hungry eye towards Psaa Nat, ranging from Chinese-backed tourist resorts and banking or electronics businesses to bars, restaurants, and phone shops operated by the family members of important local leaders. Should Psaa Nat be sold off to investors in this manner, it will dramatically alter the “Charming” quality of downtown Battambang City on which the hopes for future development hang. I cannot predict what will happen, but I sincerely hope that local government - many members of which I know personally and believe to be reasonable people who understand the problems facing reconstruction - will decide to rebuild Psaa Nat. While the loss of Psaa Nat will sting for quite some time - especially for people who worked in the market daily - the city can still salvage the market’s symbolic importance if it immediately devotes itself to rebuilding Psaa Nat with respect to its former history. While I do not necessarily advocate for an exact replica of what existed before, I do believe that intentionally referencing local history in reconstruction can be of great benefit to the city of Battambang, although I also believe this event provides a unique opportunity to improve the market space for the betterment of vendors and shoppers alike. What will be required is not so much money as moral courage - which the local populace has in abundance, but which may test local leadership. I, for one, think today of the people of Battambang as they mourn the loss of one of the city’s most important symbols. But I also assert, as I always have, that Cambodians are in control of Cambodia regardless of the opinions or influence of outsiders. In other words, I advocate for the preservation of colonial architecture but only on Khmer terms. Should locals see these buildings as emblematic of colonial oppression and wish to erase them from the face of the earth, then I fully endorse their right to do so. While I do not believe most Cambodians feel hostility towards these buildings, and believe that locals will likely want to rebuild, I also encourage them to do so with respect to their own history and the celebration of Khmer ingenuity. Replacing a colonial building with capitalist exploitation is simply another form of colonialism, and thus locals must push for a communal effort to rebuild in a way that respects history but on Khmer terms. I know the people of Battambang to be more than willing to undertake such tasks, and while I am sad to see the flames devour such an important piece of local history, I am excited to see and support my friends in Battambang as they create a new future for themselves. Let us hope that local leaders have the same vision. ---

1 - Often commonly spelled Psaar Nath or some variant, spelled ផ្សារណាត់ in Khmer. 2 - Battambang actually has more preserved pre-independence buildings than any other city in Cambodia, including the capital of Phnom Penh. And it’s not close, with Battambang having over 400 preserved buildings more than the runner up city of Kep. 3 - The temple has adorned every iteration of national flag that Cambodian has ever known. 4 - Human rights organization Global Witness has connected the expansion of Gloria Jean’s in Cambodia with a powerful member of a certain highly influential Cambodian family, but I’ll let you discover that on your own instead of stating it directly here. --- 2016. Hostile Takeover: the corporate empire of Cambodia’s ruling family. Global Witness. Bijlard, Simone. 2011. Battered Beauties: a research on French colonial markets in Cambodia. Delft: Delft University of Technology. Chhoung, Tauch. 1994. Battambang during the Time of the Lord Governor. Phnom Penh: Cedoreck. Grant Ross, Helen. 2000. Battambang, Le Bâton Perdu. Phnom Penh: 3DGraphics Publishing. Lindt, Naomi. 2011, Dec 15. “A Pocket of the Past in Battambang, Cambodia.” The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2011/12/18/travel/a-pocket-of-the-past-in-battambang-cambodia.html. Trew, Matthew J. 2019. Selling Symbols: Tourism, Heritage, and Symbolic Economy in Battambang, Cambodia. Dissertation. Madison: University of Wisconsin-Madison.

2 Comments

10/10/2022 11:52:19 am

Congress government treat offer resource. Star kitchen sit your. Religious institution region hotel sound we production.

Reply

10/16/2022 02:29:51 am

Goal short charge fish news. Identify fill quite continue rise design. Arrive despite source partner miss old yard according.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorMatthew J. Trew Archives

April 2019

Categories

All

View Disclaimer and Terms of Use |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed