|

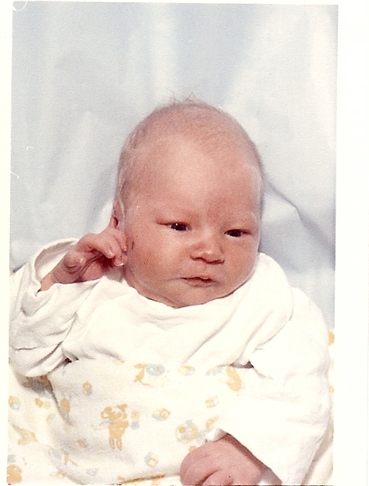

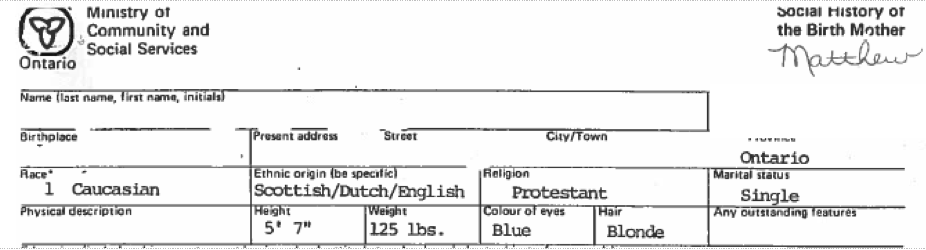

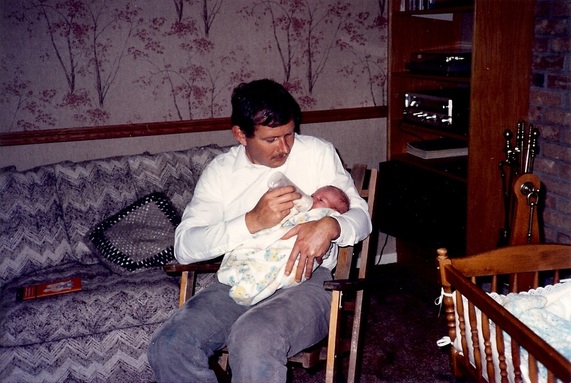

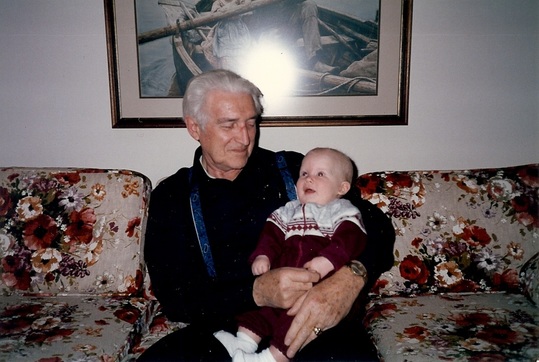

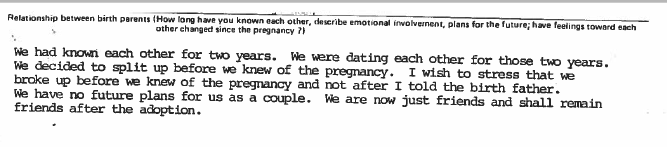

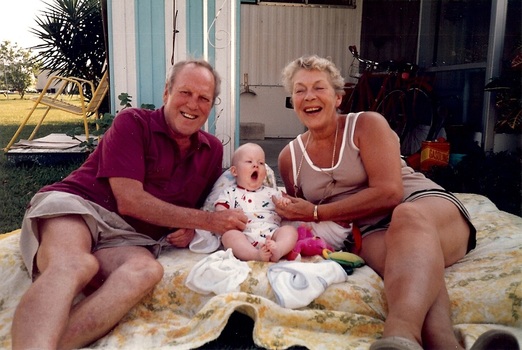

I’m adopted. I’m getting that out first because that’s how my family has always dealt with this issue – openly and without hesitation. This concept is such a part of me that it’s second nature to mention it when I meet new people. Other people are less comfortable with it than I am, however, and often double take when I say it. Almost as if they think it should be a secret or sensitive issue I wouldn’t consider normal enough to discuss in casual conversation – as if I should somehow be ashamed of it. And if that reaction wasn’t enough, they almost always ask the same follow-up question – my least favourite question to be asked, and probably the one I’m asked most often – “Don’t you want to know who your real parents are?” If you have ever wondered that question regarding adopted kids, I’m afraid I have bad news for you – you’re ignorant. Not necessarily out of malice, but certainly in such a way that reveals that you don’t understand the fluidity of the concept of family. It’s probably not your fault, though. American culture doesn’t educate about adoption particularly well, unless of course your last name is Jolie, in which case people know you as “that foreign kid someone famous decided to take in.” Which isn’t really education but rather a reduction of the complexity of your humanity into the overly simple label “adopted kid,” one who exists solely in someone else’s hero narrative. No disrespect or anything to adoptive parents, who generally are heroic, but more a comment on the systemic manner in which the public reduces this complex issue into an unsatisfying appellation. But enough about that for now. The point is, you probably don’t know much about adoption unless you are personally involved with adoption in some manner. Adoption is one of those issues still stuck in the 1950s – we’re not supposed to talk about it because it makes people uncomfortable and/or it isn’t considered important enough in the face of other issues to mention. Which is why I’ve decided to write this post about my own adoption, so that you and others can understand the adopted worldview, which is, undoubtedly, one of unique perspectives and challenges. First, though, I must fully admit that I’ve enjoyed a privileged existence in comparison to many adopted (and non-adopted!) kids. I’m a white male who was adopted into a white middle class North American family, after all, so I can’t claim to have experienced the adversity faced by those in the margins of society - especially international adoptions, which have their own sensitive cultural issues. In fact, I wouldn’t be in a position to write this piece if not for my privilege, so I want to make it clear that when I discuss the challenges stemming from my adoption, they need to be put in the proper perspective. Nevertheless, I can assert that being an adopted child, regardless of privilege, involves emotional, psychological, and spiritual obstacles unknown to non-adopted people. Not necessarily greater or more difficult obstacles, just ones that are unique to the adoption experience. The babyface of privilegeWhich brings me to my next point: there is no singular ‘adoption narrative’. Every adopted child experiences the challenges of adoption in ways dependent on their specific social position, history, etc. Even my own sister, who was adopted from a separate birth family than my own, reacted to her adoption in a dramatically different fashion than I did. So this post isn’t representative of “How Adoption Affects Kids,” which is a summary that cannot be written, but rather an exploration of how adoption affected one individual. My hope is that this story will come across as less self-serving than it may sound and instead illuminate some of the more common issues that adopted people face. I’m certain that non-adopted children will recognize many of the discussed emotional struggles of adolescence, while also learning new things about the unique challenges of adoption. Let’s start with some terminology so that you’ll be able to follow along. Many adoptive families use their own terms for specific ideas, but there are some common phrases that people generally recognize. The most important of these is the distinction between “family” and “birth/biological family.” The term “family,” or any generic marker of kinship that would be used in a typical situation, such as “mother,” “father,” “sister,” etc., are used to describe the adoptive family. In other words, the woman I refer to as “mother” never gave birth to me. The woman who did endure that labour for my existence is referred to as my “birth mother” because she is my mother only in terms of the act of giving birth. In my case, my birth mother never raised me for even a moment and my relationship with her lasted only long enough to cut the umbilical cord. For that reason, she gets the qualifying terminology. Other families with different situations might play with these terms a bit differently, but the general idea is fairly common amongst adoptive families. So now we can answer that question from earlier: do I want to know who my real parents are? Well, I already do know them. My mother and father – again, who did not conceive or birth me – are my real parents. They raised me since the moment I was born, fed me, clothed me, taught me everything I know – therefore, despite not sharing my physical blood, they’ve certainly earned the right to the title through years of putting up with me. Depicted: a real family... |

AuthorMatthew J. Trew Archives

April 2019

Categories

All

View Disclaimer and Terms of Use |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed