|

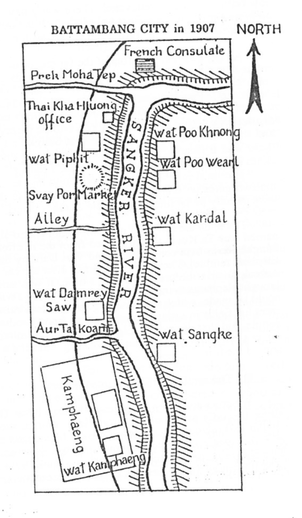

Update September 1st, 2020: as the investigation into the fire reveals more information, it seems the market is salvageable. 33 stalls were destroyed and another 44 were damaged (of the over 700 inside the building). The fire is believed to have been caused by bad electrical wiring (which is anything but surprising given the way wires work in Cambodia), and a structural assessment of the building is ongoing. The fire was largely contained to the western half, meaning that the clock tower in the eastern portion got a little dirty from smoke but seems to be standing just fine. I have heard many local friends claim that the fire may end up being a good thing, as plans are already underway to clean and paint the market to make it look even better than it did before. I am much relieved to know that the damage is not as severe as initially thought, even if some of my post is made irrelevant by that information. For the sake of posterity, and because these issues are still important to consider at the market and beyond, I am leaving this post up in its original format. Soon after 6pm on Sunday, August 30th, 2020, hundreds of Cambodians encircled Psaa Nat - the Meeting Market - and watched helplessly as flames engulfed the structure’s empty clock tower that points just ever-so-slightly southeast towards the Sangkae River. For nearly 90 years, Psaa Nat stood as one of the most iconic buildings in the northwestern Cambodian city of Battambang - visible on tourist t-shirts and postcards, and often serving as a backdrop for photos for locals and visitors alike. The cause of the fire is as-yet unknown, although there were storms in the area so lightning is a possibility, as is the spread of an open fire through the textile market from a range of sources. Unable to visit Battambang myself this summer due to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, I sat on my couch in Green Bay, Wisconsin watching in horror as my research assistant Visal sent me live photos and videos of the conflagration. Like so many residents of Battambang, I have a deeply personal connection with Psaa Nat. On my first trip to Battambang in 2009, I stayed the first night of my lifetime fascination with the city in the Royal Hotel directly adjacent to Psaa Nat’s western entrance. One of my best friends in Battambang sold clothing in the market, and I even had jewelry made there for my family on my last visit (in addition to one of my own Buddha amulets). I’ve spent countless hours sitting amongst the piles of shoes and textiles talking to vendors and shoppers about their lives, and one of my favorite picture spots in the region is directly across the river to the east facing towards Psaa Nat’s skeletal clock tower. While my grief is but a fraction of that felt by those who depended on the market for their livelihoods, I know that everyone who loves Battambang for its unique magic is heartbroken to see the images of this beloved building swallowed by unforgiving flames. The good news is that, as of this writing, there are no reported deaths caused by the fire. The bad news is that, in a summer already occupied with a seemingly unending barrage of problems, local officials estimate that the building is 80% lost and is unlikely to be saved (although damage may be largely contained in the western half without the clock tower). Not only will the loss of the market directly affect the hundreds of people directly dependent on Psaa Nat for their income, but the building’s loss creates several obstacles for urban development and the problematic politics that often occur in Cambodia. First, Battambang City is in the midst of applying for UNESCO World Heritage Status - a politically motivated designation that carries with it the potential for significant gains in tourism(both domestic and international) and urban development. Battambang markets itself as the “Charming City” - a title invented to emphasize the city’s timeless feel and highlight the hundreds of French colonial (and pre-French colonial) buildings for which the city is known. Psaa Nat was one of the most instantly recognizable of these buildings - an emblem of Battambang as a “pocket of the past,” to quote a 2011 feature piece about the city in The New York Times. The now-burned structure was designed and constructed in 1936-1937 by Jean Desbois and Louis Chauchon, who were also responsible for Cambodia’s most famous market - the contemporaneous Psaa Thmei (New Market) in Phnom Penh. The market was built in two halves, with the larger western half containing most of the stalls and the smaller eastern half containing enclosed shop space at the end, adorned by an art deco clocktower. The walkway separating the two parts became an open-air food market, and one of the best places in town to sit, eat some authentic Khmer cuisine, and watch people go about their business. During the violent Khmer Rouge regime in the late 1970s, most of the market’s adornments were removed, leaving behind bare concrete walls and the cut-outs that once housed the clock mechanism. The resulting tower thus became a photogenic symbol of local history ranging from colonial occupation to genocidal conflict to recent recovery. While most people assume the French built the market, it’s important to note that the French are actually only responsible for the market building itself. Before the French took control of the region in 1907, Battambang was ruled as a quasi-independent tributary state by the Aphaiwong dynasty, who were Khmer born but loyal to the Thai monarchy. Maps from this period indicate that the land upon which the French built Psaa Nat was designated a market space far before French arrival, and thus it may be said that the Khmer (with Thai influence) organized Battambang’s downtown heritage district in whilst the French merely built up those foundations into what most people recognize today. Nevertheless, the complicated historical narrative represented by Psaa Nat is precisely what appeals to organizations like UNESCO and could transform Battambang into an internationally-known heritage city. While many other buildings still exist from that time period, the loss of Psaa Nat will certainly force the city to revise its UNESCO strategy. In so doing, a new danger arises: the blight of corruption in Cambodian urban development. Gut reaction tells me that most residents of Battambang will want to rebuild Psaa Nat, assuming most of it cannot be saved. As an icon of their city, of which I have always known them to be extremely proud, Psaa Nat carries deep meaning for locals and they will not let it go easily. Furthermore, Cambodians care deeply about architectural heritage, inspired in part by the importance of Angkor Wat in nationalistic iconography. When the cathedral of Notre-Dame burned in Paris in April 2019, most Cambodians I knew openly mourned the loss of such a great religious structure - even if (and perhaps partly because) it represented a foreign religion from a country that once imposed itself on them. Most of my Cambodian friends changed their social media profile photos and retweeted hashtags to empathize with the French. No one is likely to do the same for the people of Battambang, but locals will mourn their loss in much the same way that the world mourned for Paris. Unfortunately, even if the people of Battambang want to rebuild the market, it is not a guarantee. Psaa Nat occupies prime real estate in the direct heart of Battambang’s heritage district. A large plot of land near the river and other important government buildings, the temptation to sell the land for a profit will loom large over local government. In recent years, Cambodian officials have been heavily criticized for selling off land (occupied or not) to foreign investors, and for tearing down important buildings (such as the White Building in Phnom Penh) for dubious reasons - with bribery and kickbacks being obvious but never explicitly stated reasons. Battambang is no stranger to this behavior, as a Gloria Jean’s Coffee took over one of the most picturesque former colonial buildings along the waterfront in 2016, with a KFC soon following nearby, despite local protests. Standing kitty-corner to Psaa Nat’s western entrance, the Green Tower - so called because of the green construction tarps draped over it - has stood empty for nearly a decade, having been poised to become the city’s tallest building (again, despite local protest) but abandoned due to financial collapse before the walls were finished. Numerous investors will undoubtedly turn a hungry eye towards Psaa Nat, ranging from Chinese-backed tourist resorts and banking or electronics businesses to bars, restaurants, and phone shops operated by the family members of important local leaders. Should Psaa Nat be sold off to investors in this manner, it will dramatically alter the “Charming” quality of downtown Battambang City on which the hopes for future development hang. I cannot predict what will happen, but I sincerely hope that local government - many members of which I know personally and believe to be reasonable people who understand the problems facing reconstruction - will decide to rebuild Psaa Nat. While the loss of Psaa Nat will sting for quite some time - especially for people who worked in the market daily - the city can still salvage the market’s symbolic importance if it immediately devotes itself to rebuilding Psaa Nat with respect to its former history. While I do not necessarily advocate for an exact replica of what existed before, I do believe that intentionally referencing local history in reconstruction can be of great benefit to the city of Battambang, although I also believe this event provides a unique opportunity to improve the market space for the betterment of vendors and shoppers alike. What will be required is not so much money as moral courage - which the local populace has in abundance, but which may test local leadership. I, for one, think today of the people of Battambang as they mourn the loss of one of the city’s most important symbols. But I also assert, as I always have, that Cambodians are in control of Cambodia regardless of the opinions or influence of outsiders. In other words, I advocate for the preservation of colonial architecture but only on Khmer terms. Should locals see these buildings as emblematic of colonial oppression and wish to erase them from the face of the earth, then I fully endorse their right to do so. While I do not believe most Cambodians feel hostility towards these buildings, and believe that locals will likely want to rebuild, I also encourage them to do so with respect to their own history and the celebration of Khmer ingenuity. Replacing a colonial building with capitalist exploitation is simply another form of colonialism, and thus locals must push for a communal effort to rebuild in a way that respects history but on Khmer terms. I know the people of Battambang to be more than willing to undertake such tasks, and while I am sad to see the flames devour such an important piece of local history, I am excited to see and support my friends in Battambang as they create a new future for themselves. Let us hope that local leaders have the same vision. ---

1 - Often commonly spelled Psaar Nath or some variant, spelled ផ្សារណាត់ in Khmer. 2 - Battambang actually has more preserved pre-independence buildings than any other city in Cambodia, including the capital of Phnom Penh. And it’s not close, with Battambang having over 400 preserved buildings more than the runner up city of Kep. 3 - The temple has adorned every iteration of national flag that Cambodian has ever known. 4 - Human rights organization Global Witness has connected the expansion of Gloria Jean’s in Cambodia with a powerful member of a certain highly influential Cambodian family, but I’ll let you discover that on your own instead of stating it directly here. --- 2016. Hostile Takeover: the corporate empire of Cambodia’s ruling family. Global Witness. Bijlard, Simone. 2011. Battered Beauties: a research on French colonial markets in Cambodia. Delft: Delft University of Technology. Chhoung, Tauch. 1994. Battambang during the Time of the Lord Governor. Phnom Penh: Cedoreck. Grant Ross, Helen. 2000. Battambang, Le Bâton Perdu. Phnom Penh: 3DGraphics Publishing. Lindt, Naomi. 2011, Dec 15. “A Pocket of the Past in Battambang, Cambodia.” The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2011/12/18/travel/a-pocket-of-the-past-in-battambang-cambodia.html. Trew, Matthew J. 2019. Selling Symbols: Tourism, Heritage, and Symbolic Economy in Battambang, Cambodia. Dissertation. Madison: University of Wisconsin-Madison.

2 Comments

Greetings once again, friends and fellow adventurers! After several years away, I’ve finally decided to revamp this website and start writing again. Apologies for being away so long, but life has been a bit of a roller coaster the past two years or so and I’m only now starting to settle down and let my head clear. I’ve cleaned up some of the past postings, so for the few of you who actually missed reading my thoughts and musings, please bear with me for a little while as I try to get this site going again and re-fill the content. I wish I had a better occasion for my return but, honestly, I decided to write again because today is the 20th anniversary of the massacre at Columbine High School – an event that deeply affected me when I was younger, as I’m sure it did you. Normally, I wouldn’t comment on this event, but I was actually in the Denver area last month and decided to visit Columbine High School and the memorial they’ve established to the events of two decades ago, so I thought it might be an interesting way to merge my personal interests with my professional life to briefly remark on that experience and what I find to be the more optimistic aspects of dark tourism, a term you may be familiar with thanks to a recent Netflix show on the subject (which I do NOT recommend). I’m not going to rehash the entire tragedy, which is well known to most people of my generation, because it would seem exploitative and impossible given its complexity. I have no connection to the event and no real right to it, as I was living almost 1,800 miles away on the South Carolina coast at the time. I will say that, when I knew I would be in the Denver area for work and decided to visit Columbine High, I bought and read the book Columbine by Dave Cullen, who was one of the journalists actually on the scene twenty years ago. I recommend the book if you are interested in this event and want a fair accounting of what happened along with thoughtful questions about our communal misunderstandings of the tragedy, as well as some insightful commentary about what has happened in that community more recently. Cullen has some controversial viewpoints and I can’t claim to agree with everything he says – for example, I find him conflicting in how he ascribes the violence purely to psychopathy, and yet struggles to resolve this perspective with respect to the offenders’ social network – but I am convinced by several of his most important points. According to Cullen:

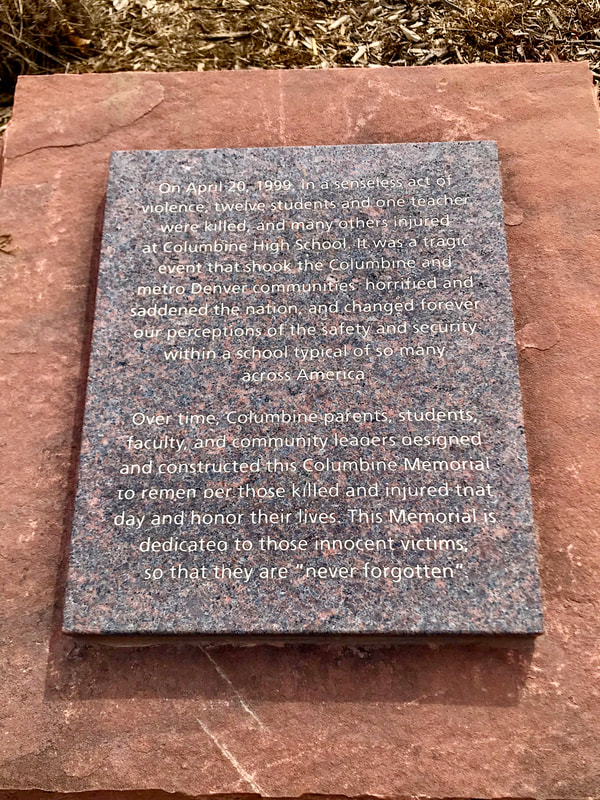

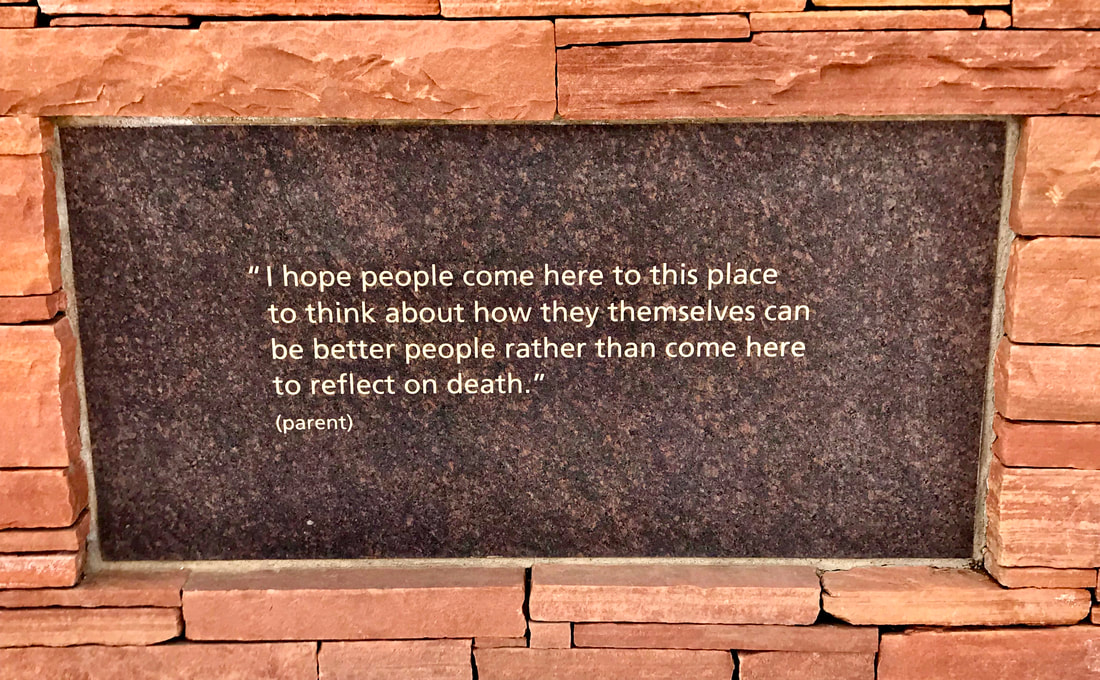

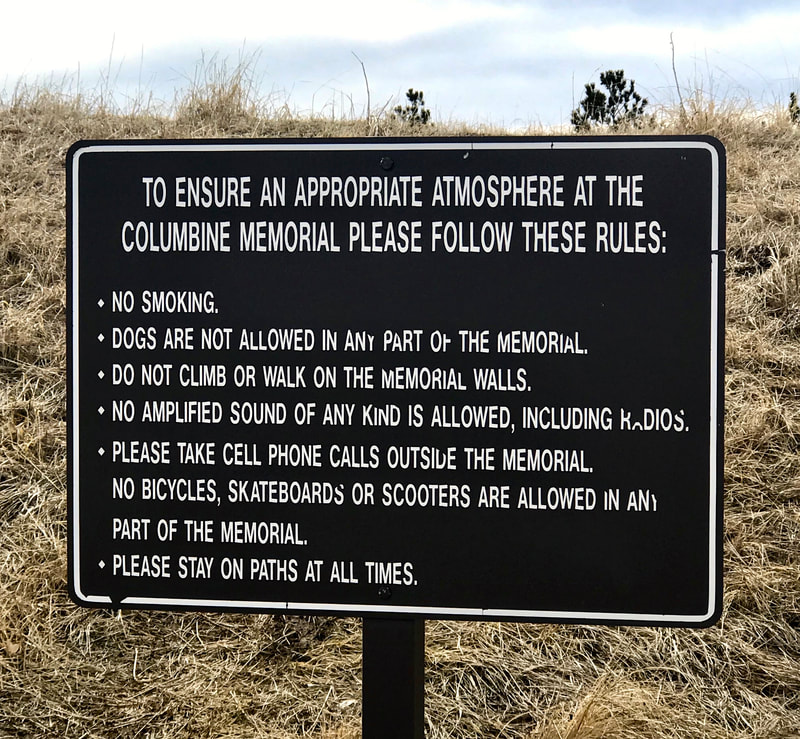

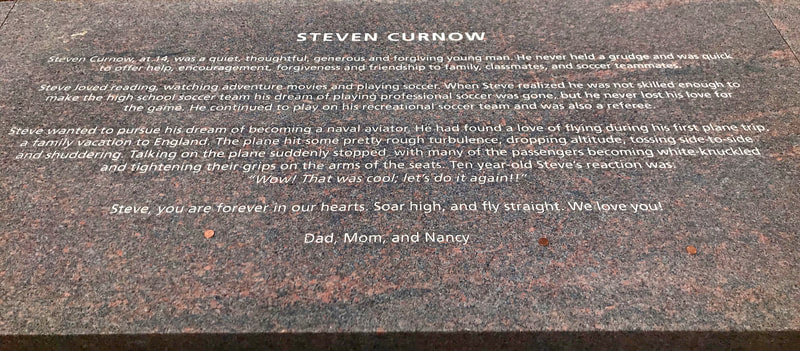

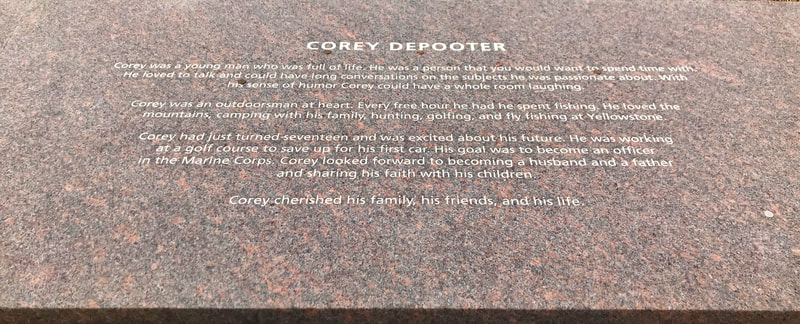

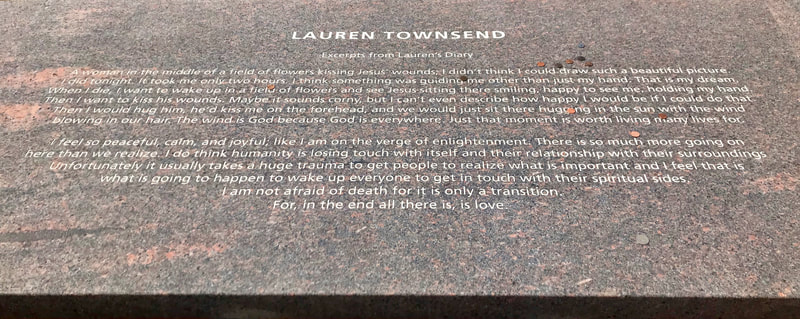

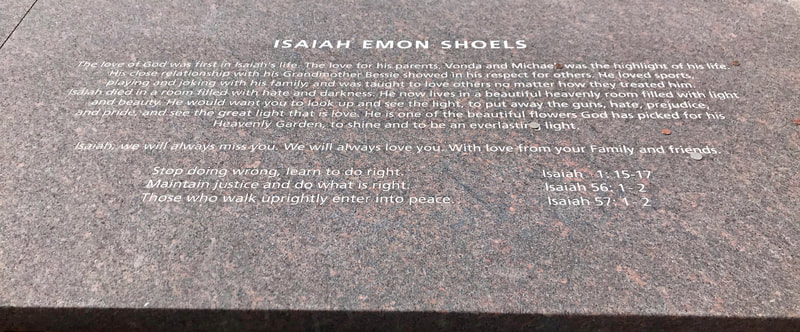

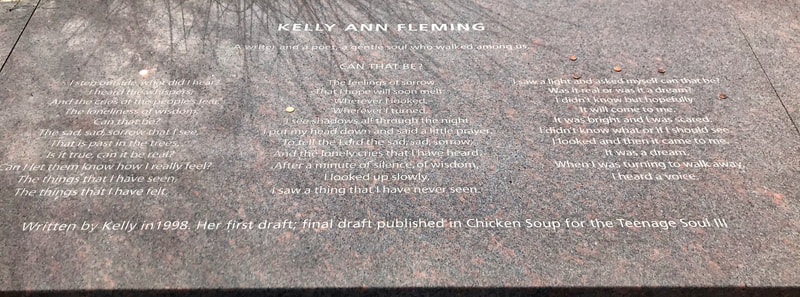

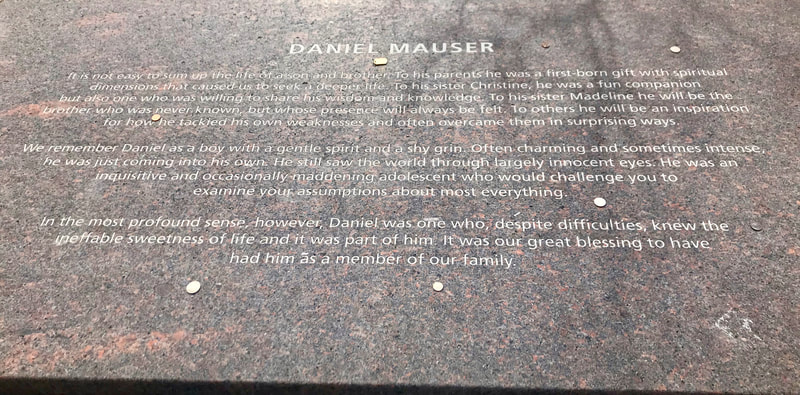

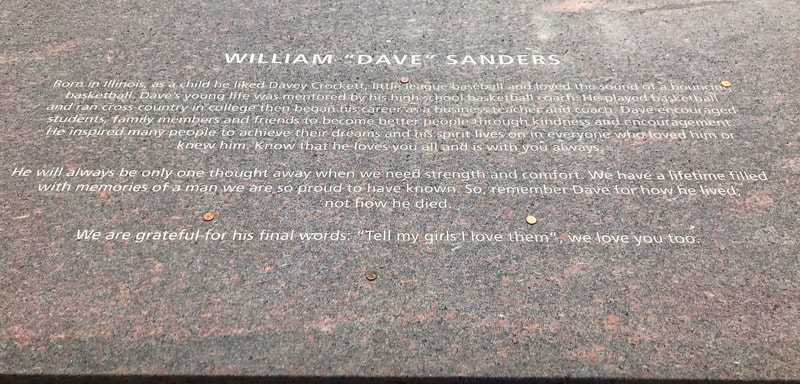

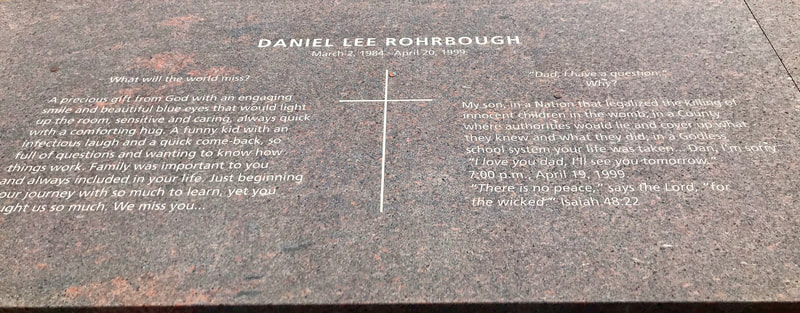

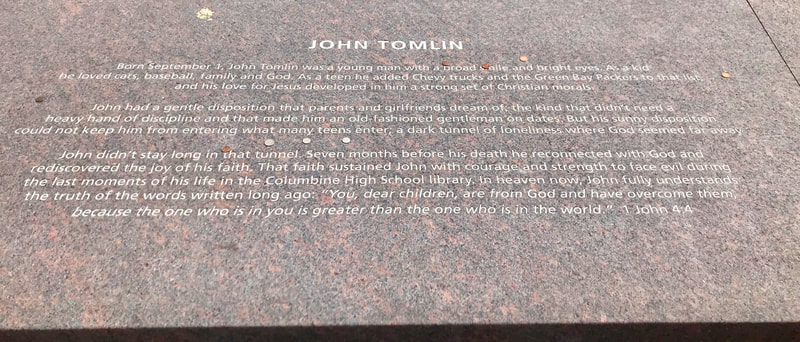

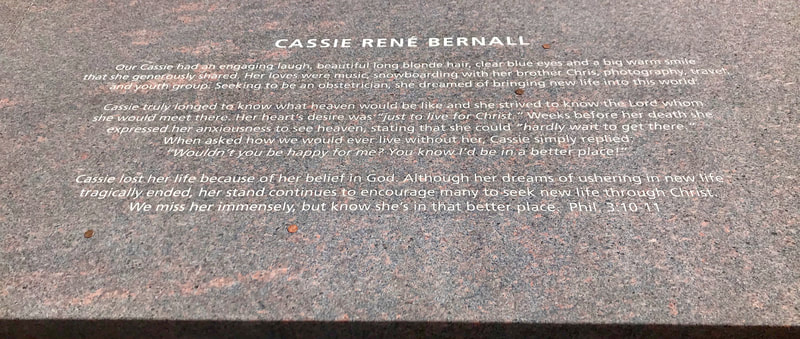

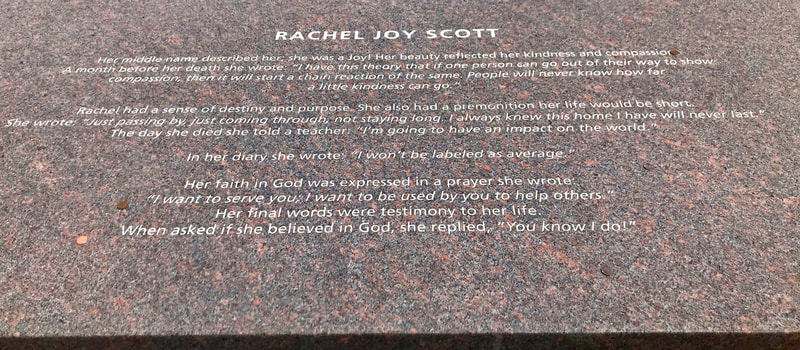

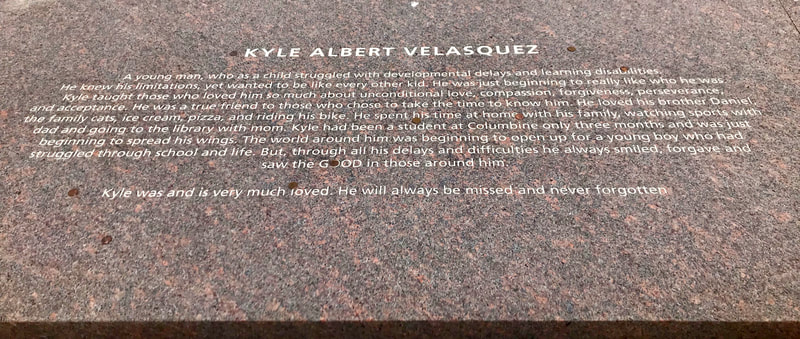

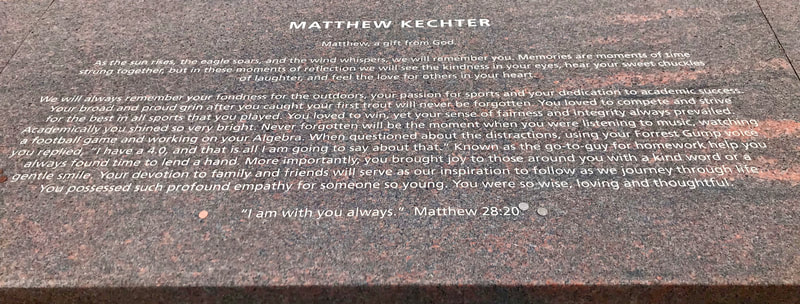

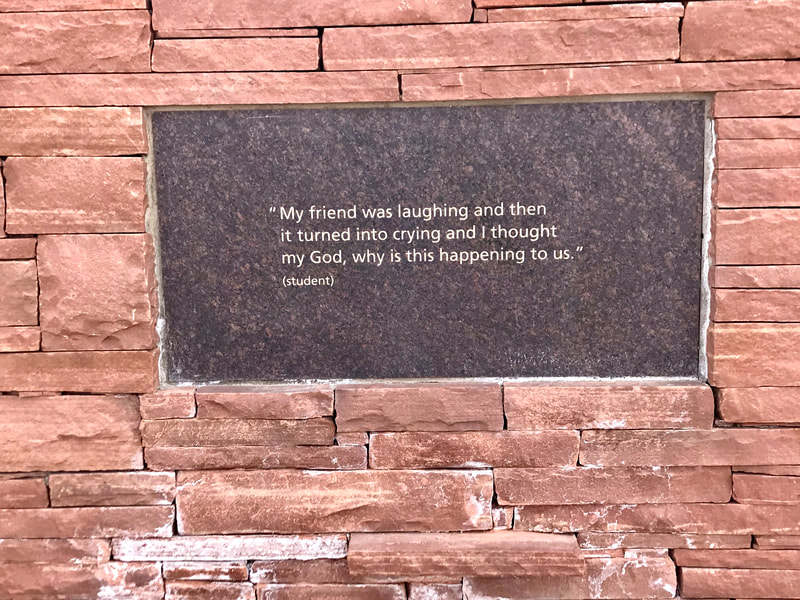

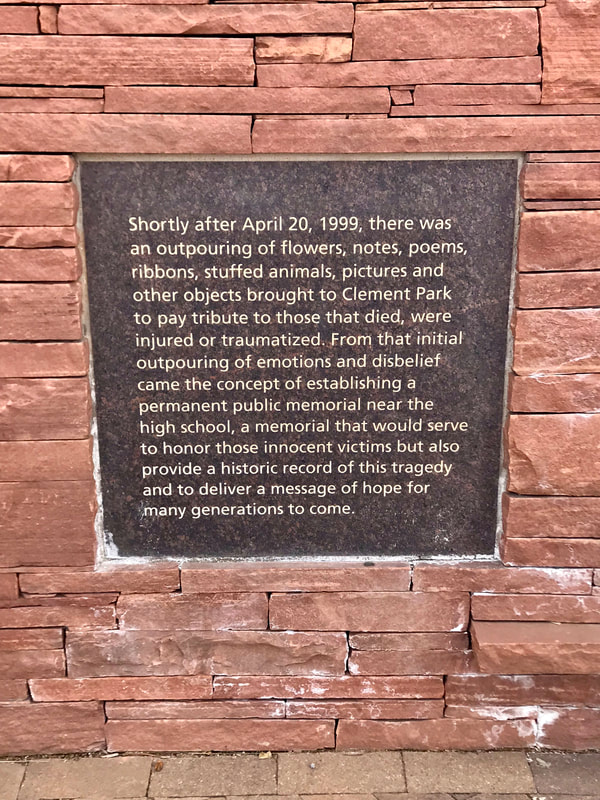

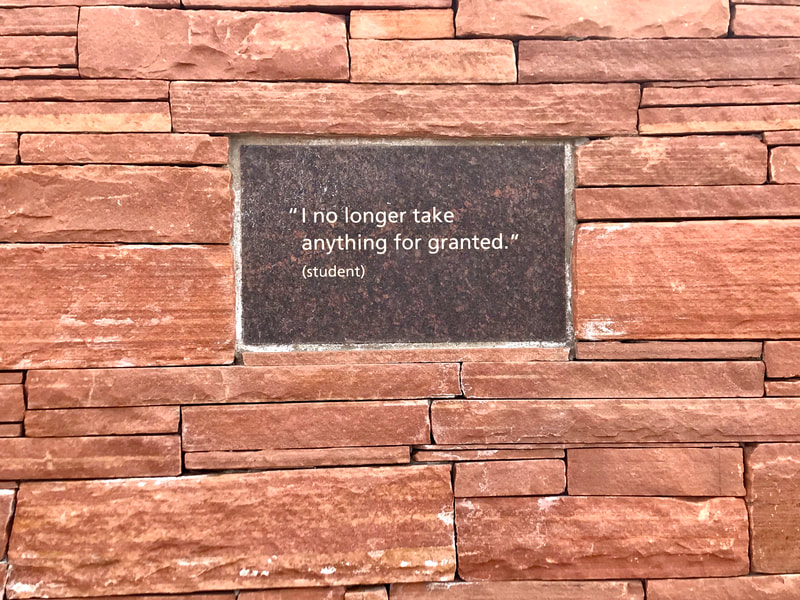

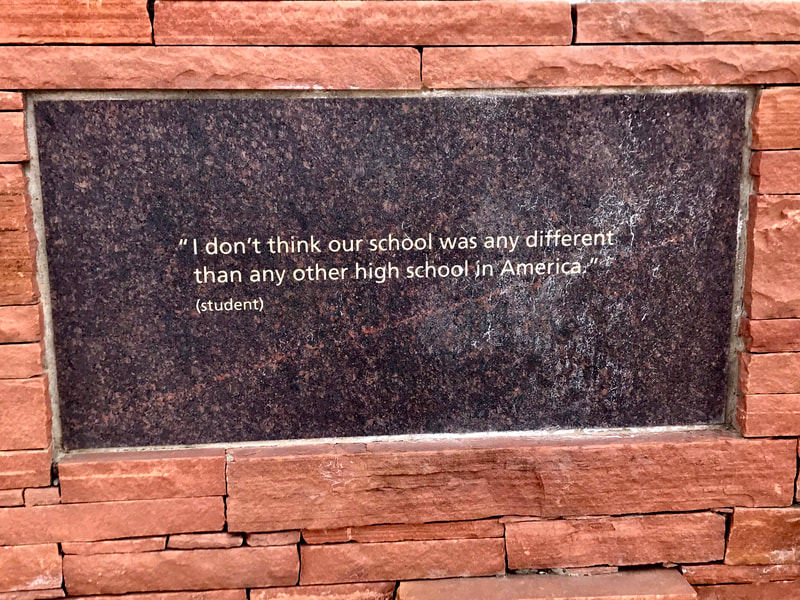

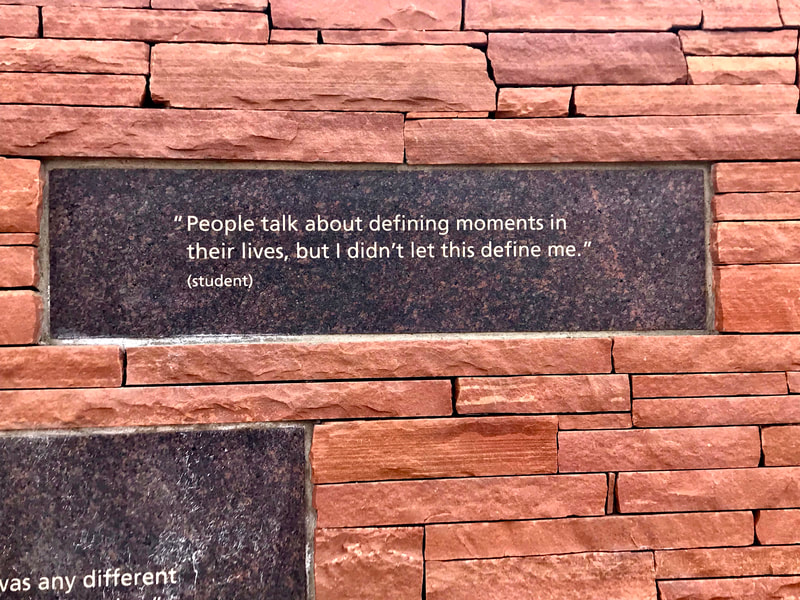

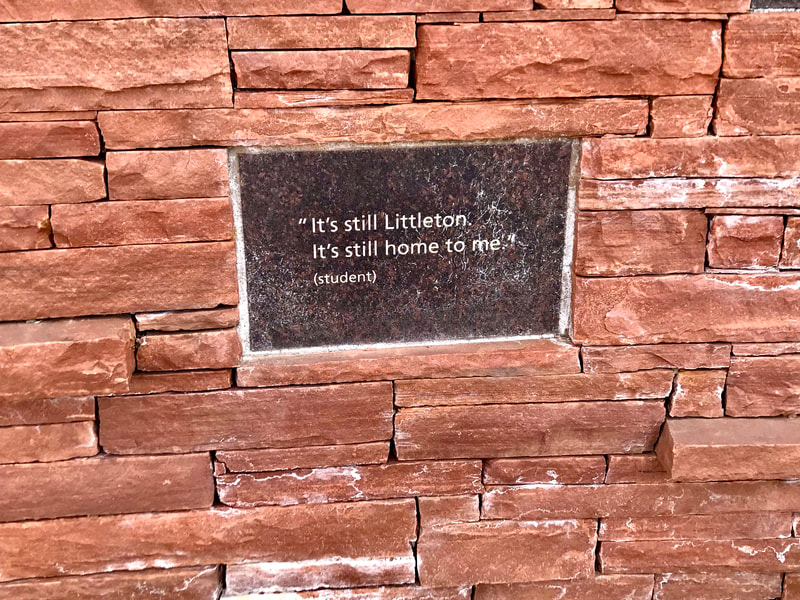

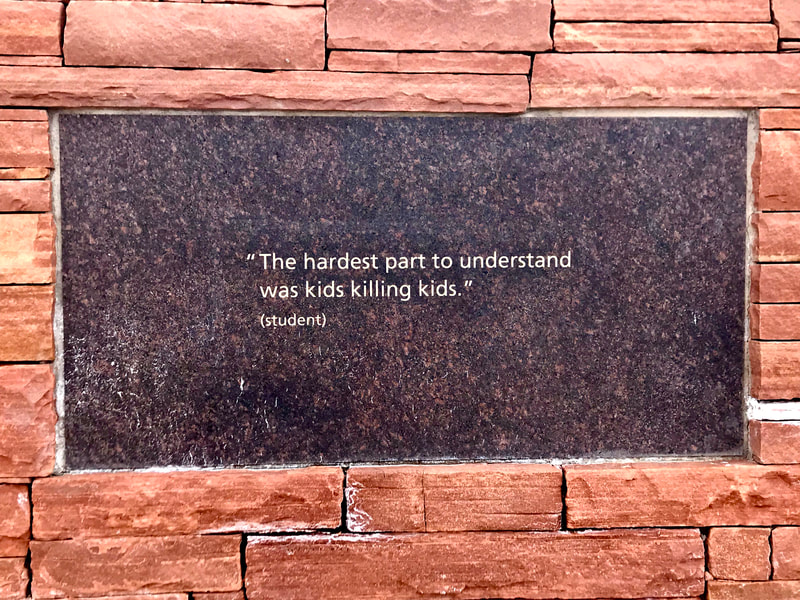

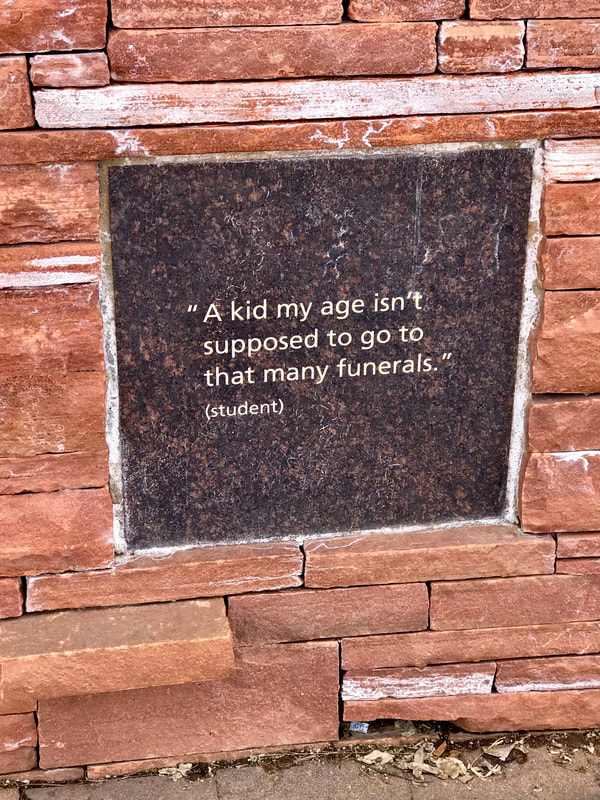

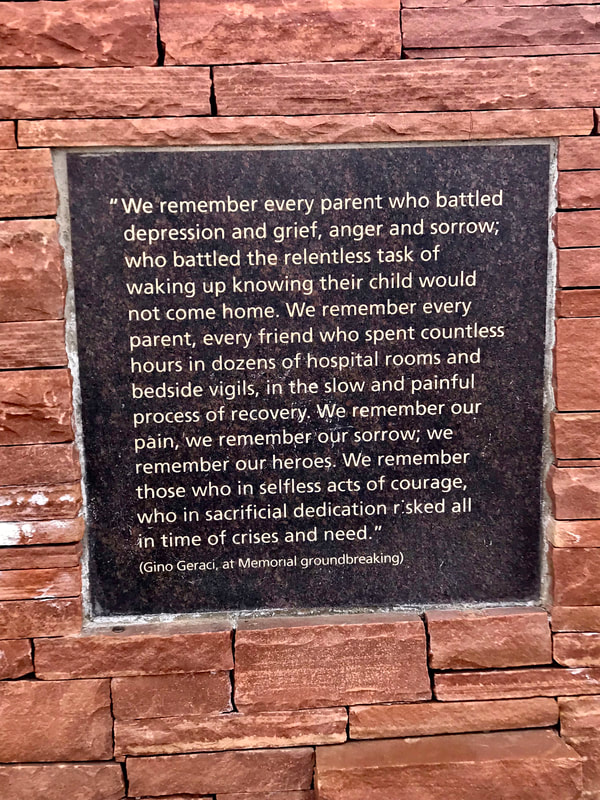

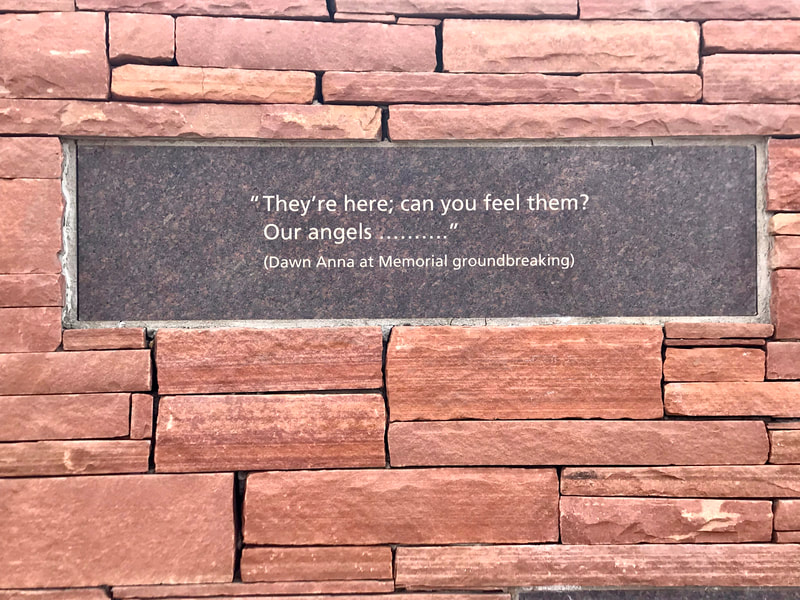

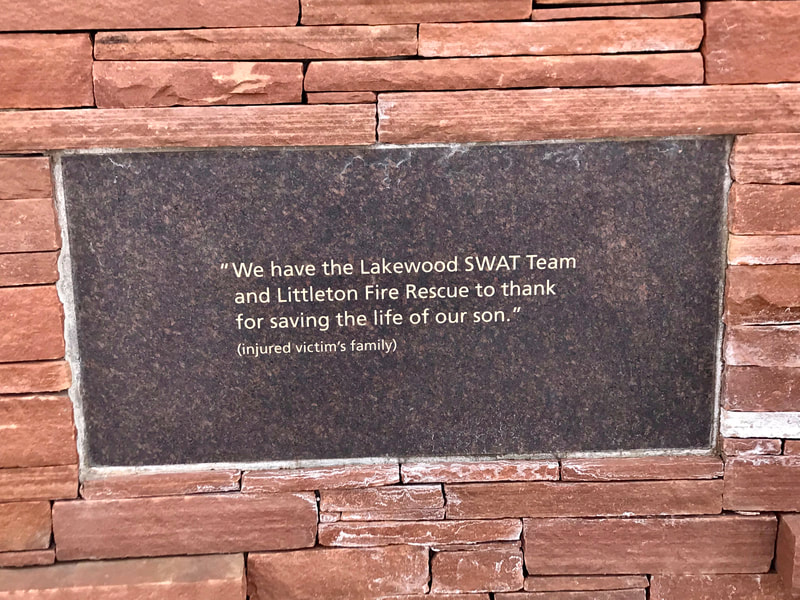

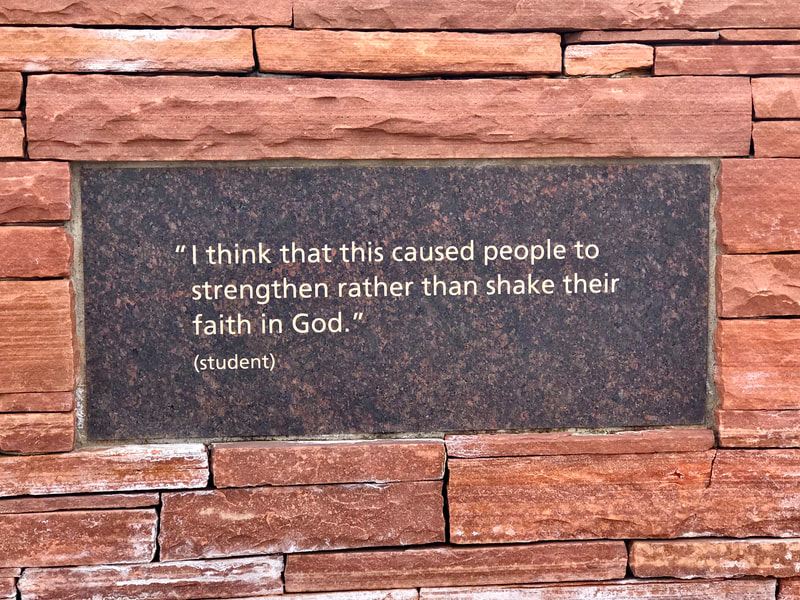

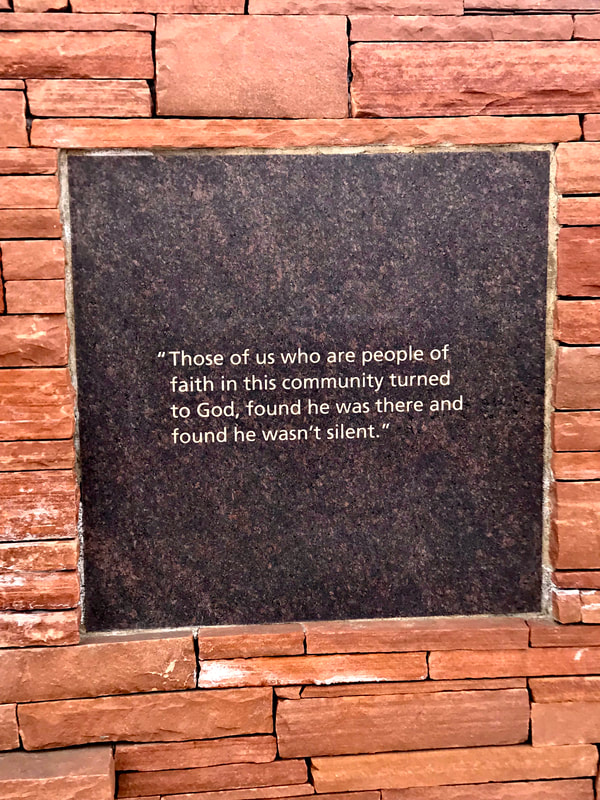

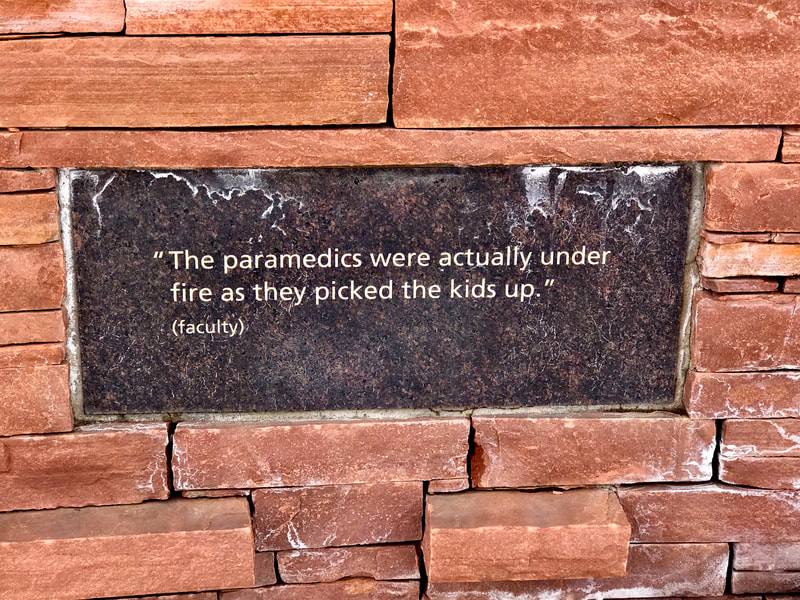

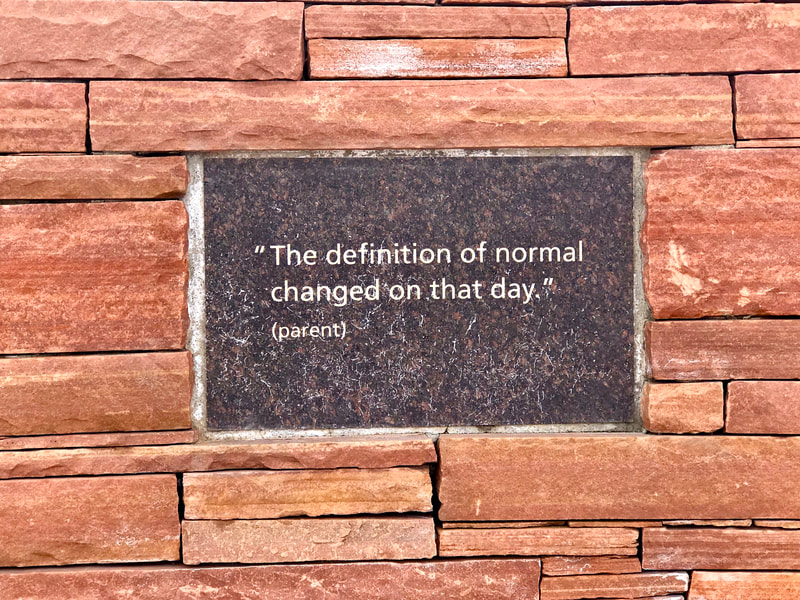

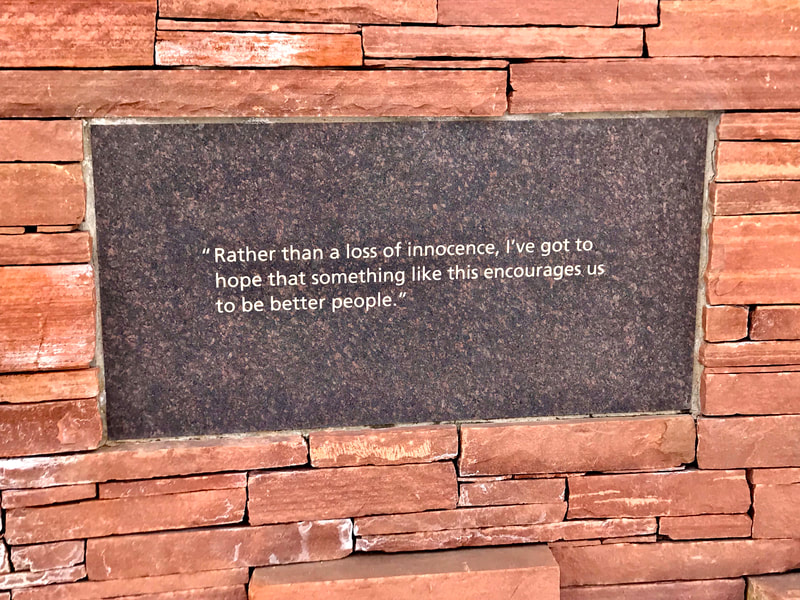

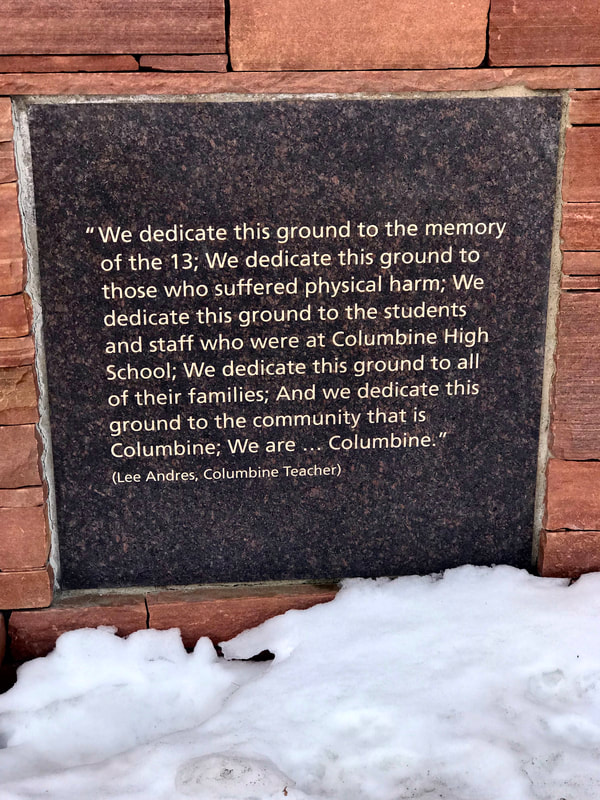

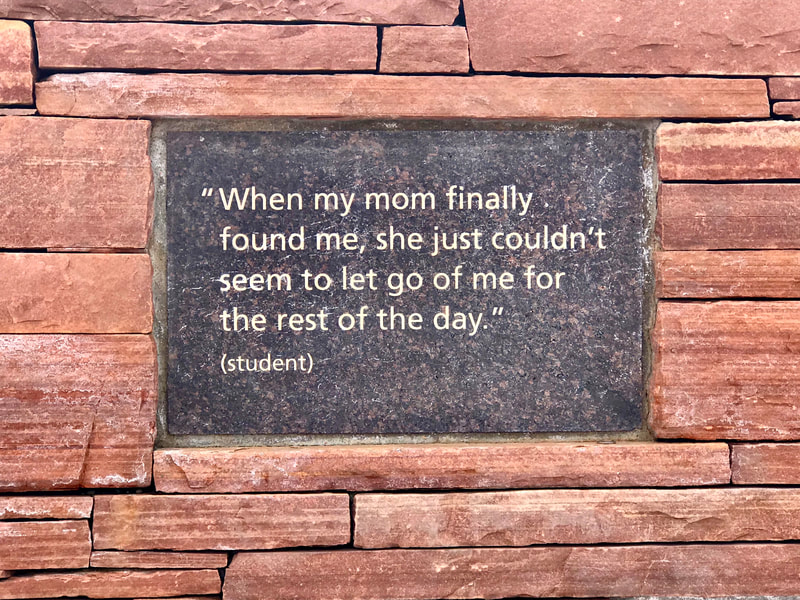

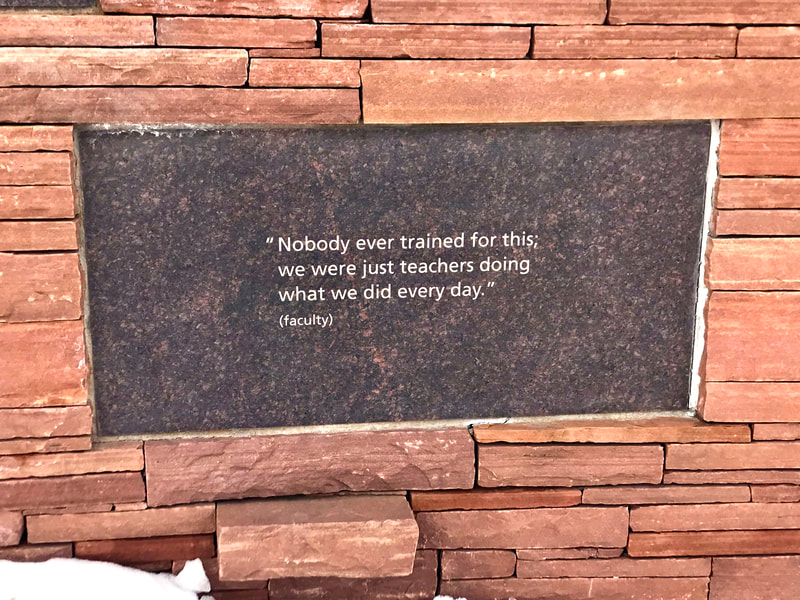

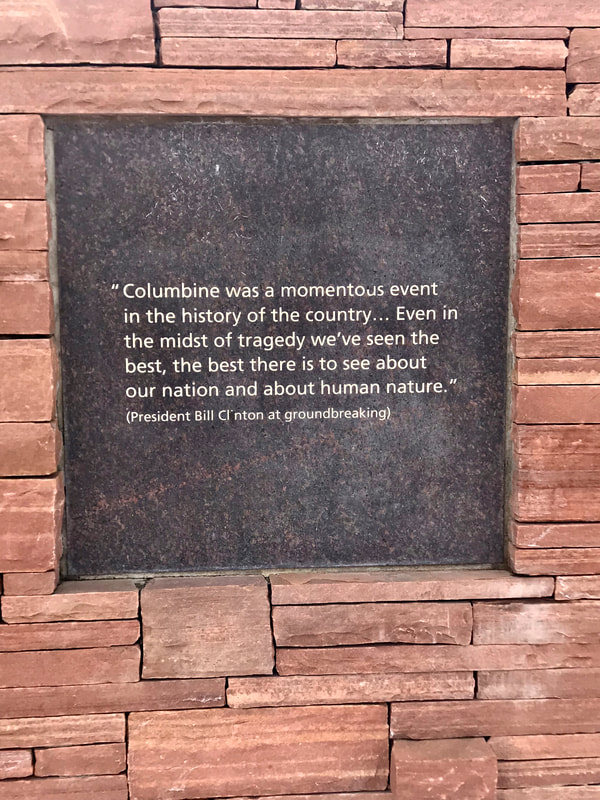

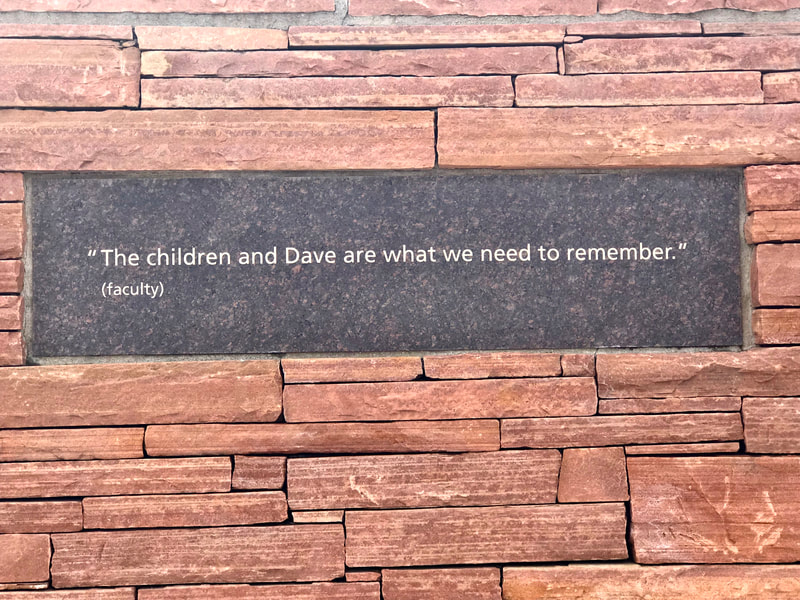

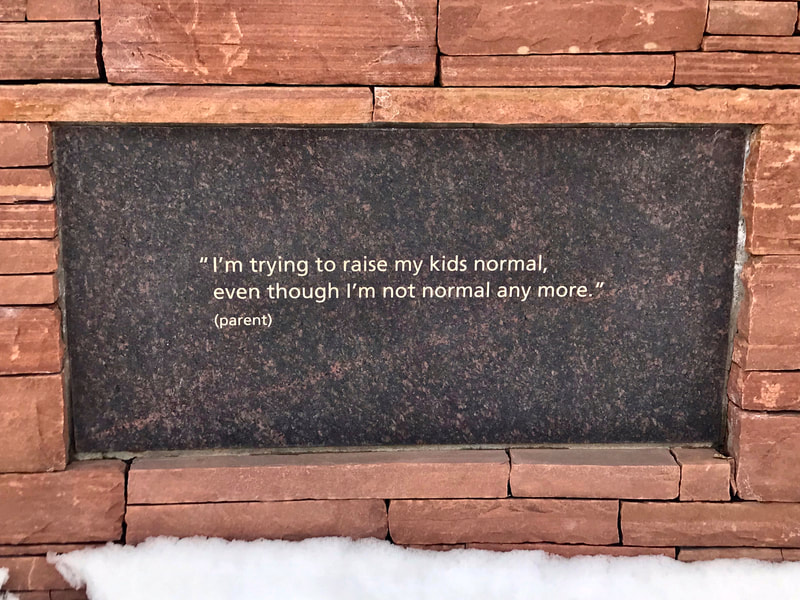

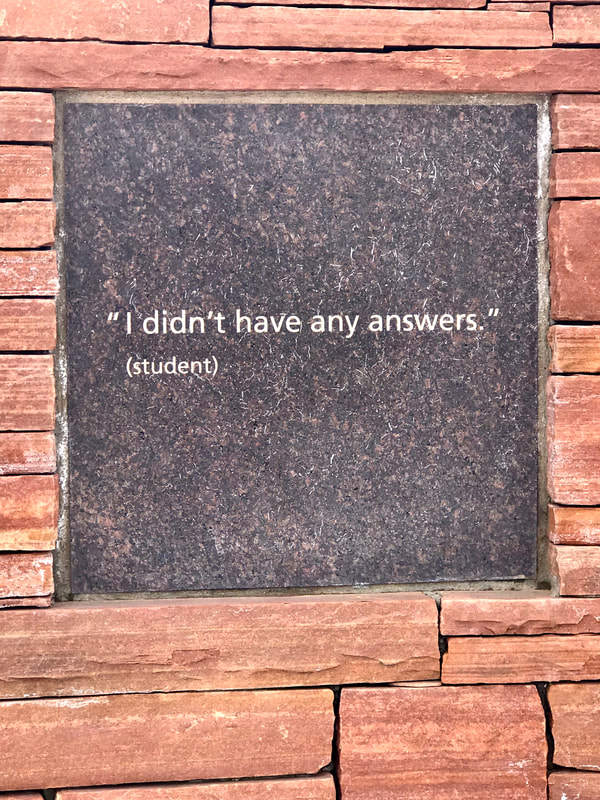

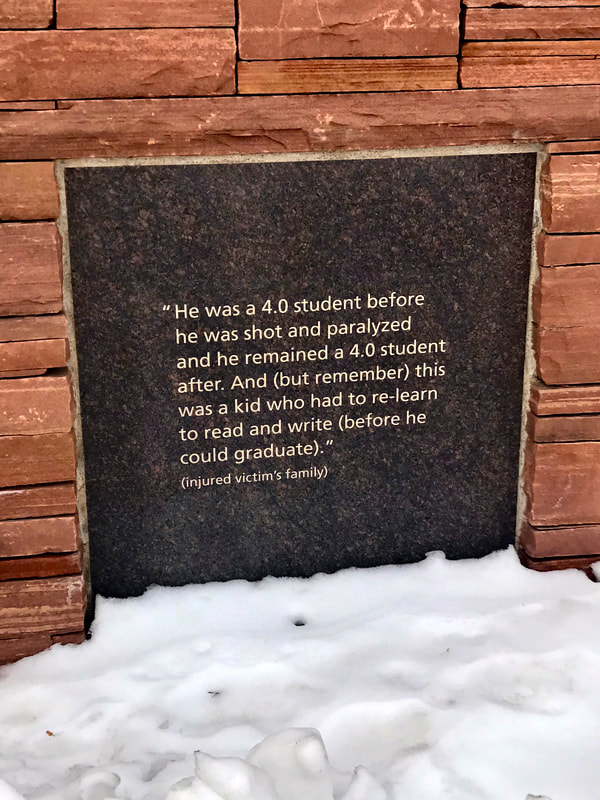

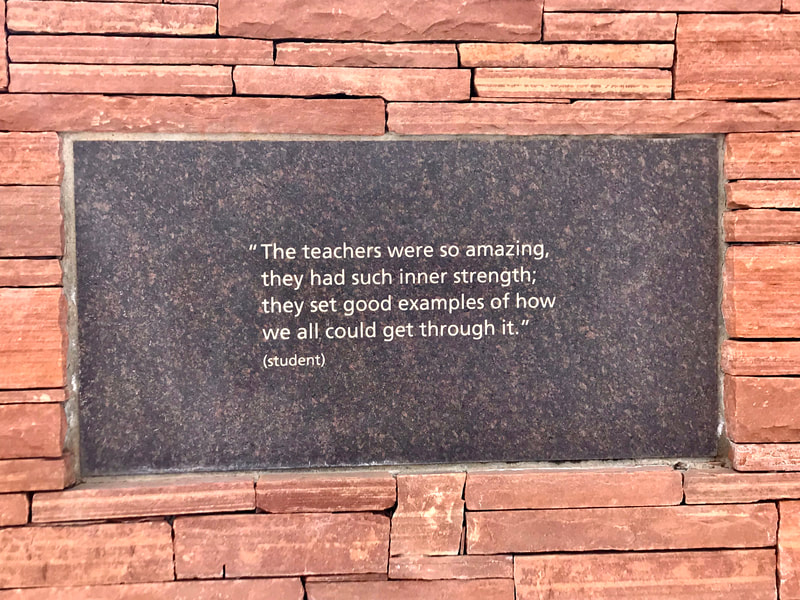

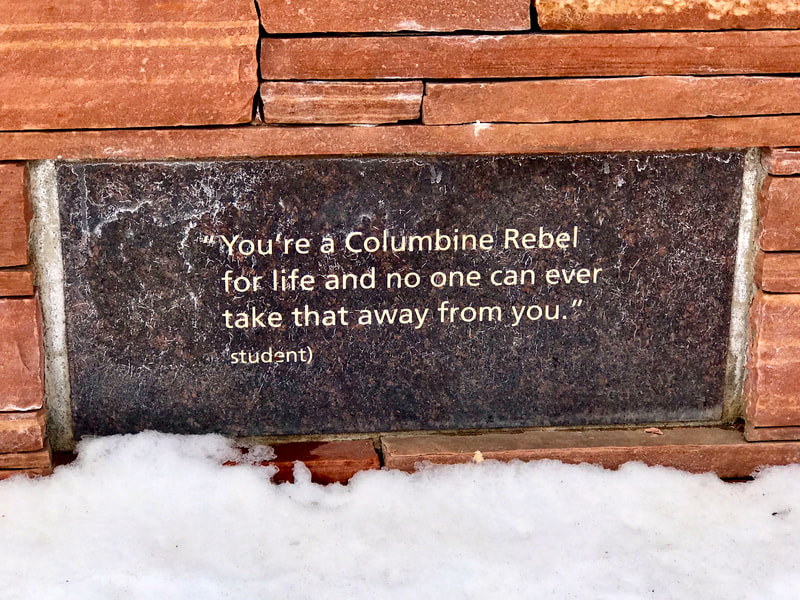

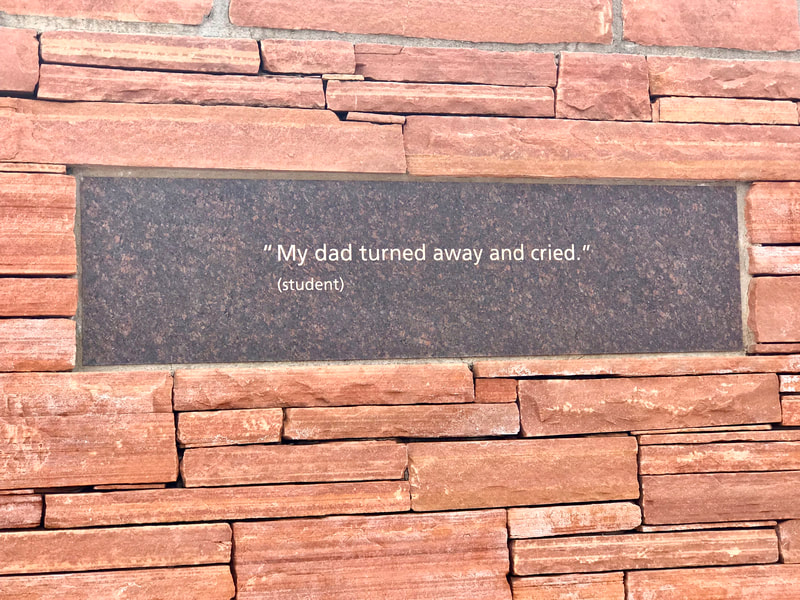

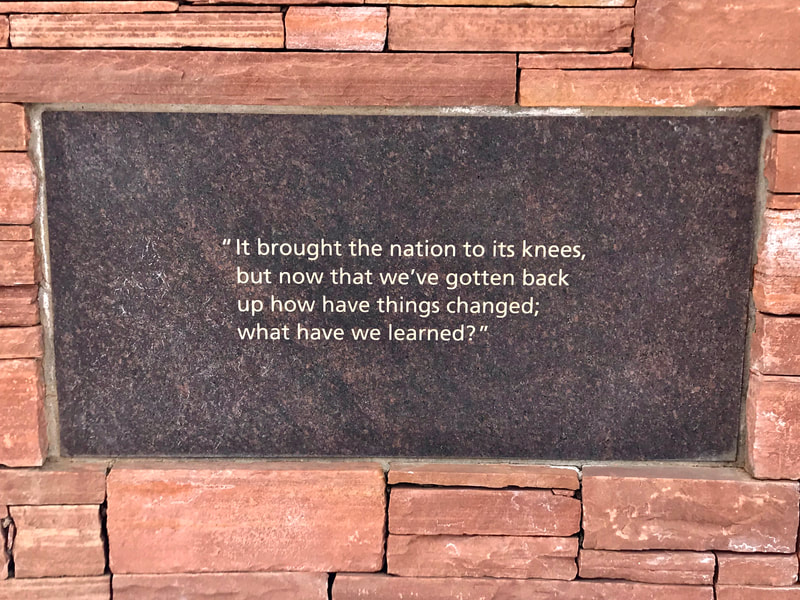

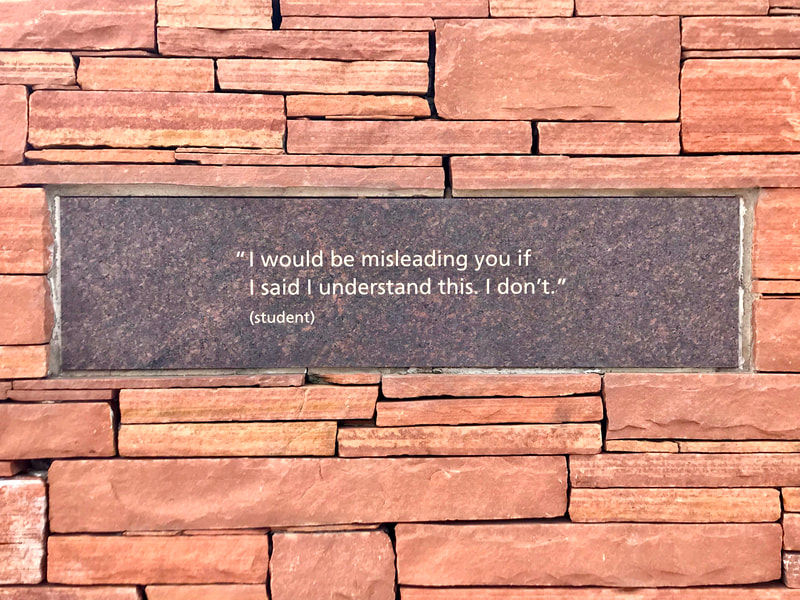

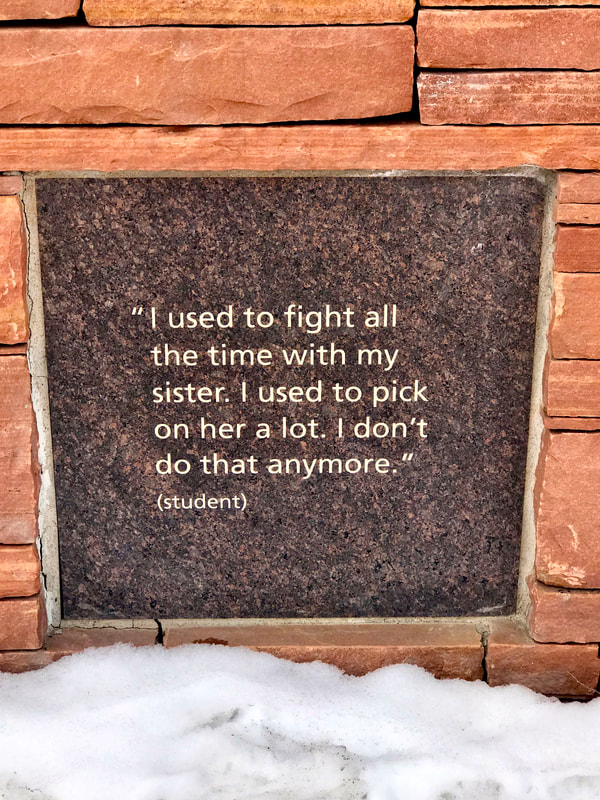

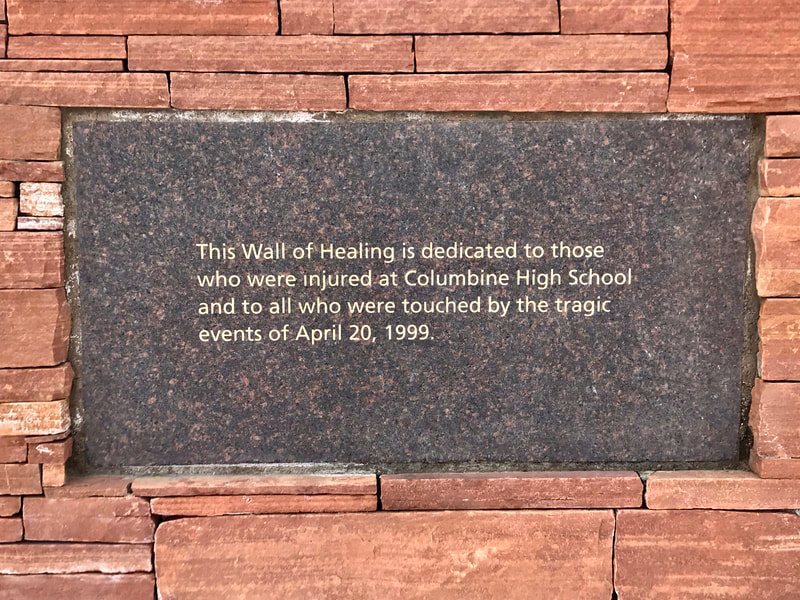

From an anthropological standpoint, I see Columbine as an example of how communities come together even in the darkest of circumstances. My specific focus in anthropology returns to this theme in numerous ways, as I am a specialist on Cambodia, which endured a genocide in the 1970s that resulted in millions of deaths, as well as someone who studies dark tourism, which Professor of Tourism and Development at the University of Central Lancashire Richard Sharpley describes as “travel…towards sites, attractions or events that are linked in one way or another with death, suffering, violence or disaster” (Sharpley 2009: 2). In my capacity as a researcher, and as someone with an interest in the human experience at such sites, I have visited numerous places of death, from serious to humorous – for example, the mass graves of Chhoung Ek, commonly known as The Killing Fields, in Phnom Penh, Cambodia; Wounded Knee on the Pine Ridge Reservation where American troops slaughtered hundreds of Native Americans, mostly unarmed women, children, and old men; the cemetery of Key West, Florida, where graves from the USS Maine are buried near the remains of former slaves and others who died in the Jim Crow era (plus a famous tombstone that reads “I told you I was sick!”); the grave of Martin Luther King, Jr., outside the Ebenezer Baptist Church where you can sit in a pew and listen to recordings of his sermons; Mount Moriah Cemetery in Deadwood, South Dakota, where colorful characters like Wild Bill Hickok and Calamity Jane are buried; the Winchester Mansion in San Jose, California, which is supposedly the 'most haunted house in America'; and so on. From ghost tours to memorials to great tragedy, I try to run the gamut of the dark tourist experience whenever possible. My approach towards going to these places is rather Zen-like: you must experience them with an open heart and open mind, accepting your feelings in full whatever they may be and then letting them go when it is their time to leave. In this way, you appreciate what the experience teaches you and carry forth the lessons therein but also recognize that tears – of which there are many – need not be permanent. I often find that tears, smiles, and even joyous laughter are not mutually exclusive even in these places of death, and there's something deeply uplifting about crying your heart out only to smile and even laugh at the smallest of silver linings in a place that might otherwise appear to have none. Such experiences are cleansing. Sometimes it’s good to feel bad, to lose your mind to your grief temporarily, and to then realize that you can put yourself back together again. My desire to visit Columbine was certainly motivated in part by my desire to confront and reframe my emotions about the massacre, which I consider a seminal event from my childhood that I care about far more than most other tragedies (not to sound callous or anything), and the visit absolutely accomplished those aims. Like many others, I hold am fascinated by tragic events, especially cult-like activities such as Jonestown and Waco, which I think are feelings that stem from a natural human curiosity about the extreme behavior of others. There's also a sympathy there, and I often find myself empathizing with victims and perpetrators alike as there are usually social factors in their decision making that are familiar to my own experience, even if we made radically different decisions along the way. Even with Columbine, I find myself rejecting the labels of inhumanity placed on the shooters because what they did, depressing or not, was an extremely human act with deeply human consequences. Although not a cult, Columbine is a moment that created a community more than destroyed it, and I find myself attracted to such a powerful magnet of human adaptability. Columbine is in the town of Littleton a few miles south of Denver, Colorado, with the Rocky Mountains looming in the background as they tend to do in this region. I find it interesting that the details we miss in video footage of tragic events like Columbine are usually the things we focus on in person. For example, to me the news footage of the massacre at Columbine makes the school seem almost secluded. We see students running from the building through large grassy fields, exposed to occasional gunfire from the upper story windows. This grassy area is Clement Park and does indeed surround the school with lots of green, but on the other side of the school are residential areas that push right up to the school grounds. It’s actually quite a busy street that passes by the front of the school, with lots of activity from cars and pedestrians. And, of course, since most news footage is shot from the top down perspective of people in helicopters, we lose the perspective of the Rocky Mountains, which are visible from a hill near the school and provide a gorgeous backdrop. In many ways, I think Columbine High School is one of the prettiest school campuses I’ve ever seen, as many of the classrooms face the mountains – far better than the parking lot I used to stare at during math class. Clement Park, where most of the survivors fled, is an active recreational center with sports fields and walking trails. Even on the cold day in early spring when I visited, the park was quite busy with visitors. Families were picnicking, the fields were being prepared for baseball games and other sports, and lots of runners and walkers were using the trails – including a large number of older couples, which added a sense of gentility to the place. Unlike other memorial sites that I’ve visited, Clement Park in no way felt like a place of sadness. Yes, many people stopped near the Columbine Memorial to respectfully read the inscription or take a moment of reflection, but the general mood was jovial. This park is the beating heart of the community, and it showed. At the top of a tall hill – the same hill, in fact, where the crosses were once placed – is the Columbine Memorial, the official monument to the tragedy. Access is open to all visitors, although park signs are placed around the memorial instructing people on proper behavior – no loud music or cell phone usage within the memorial space, for example. The memorial is carved out of the backside of the hill such that when you are viewing the memorial itself, you cannot actually see Columbine High School. The intention seems to be that your focus in this moment should be on the individualities of the victims, not on the broader presence of the school or the sensationalized details of its spatial history. In this area is an inner circle consisting of a ring of thirteen plaques for each of the victims, adorned with a personalized inscription by their families. Cullen provides a wonderful discussion of the politics of these inscriptions in his book, again showing that something so seemingly simple as memorializing the dead is anything but easy. The ground is inlaid with the form of a large memorial ribbon with a heart shape at the top, and fountains are nearby for aesthetic effect (though they were turned off during our visit due to the cold). An exterior wall includes numerous plaques with quotes from the community, praising the efforts of first responders and urging people to remember what happened here. The design is well-conceived, as the words of members of the community - first responders, parents, other students, etc. - literally wrap around the victims in a supportive embrace. The inner circle with the individual plaques is decorated with items left by visitors. Each of the names was covered in coins (which you can see in the gallery at the bottom of this post), and in one case, a dog tag left for a student who wanted to join the military. The number of the coins indicated that people often visit and leave their offerings – I suspect that many members of the community make regular visits here. The site is simple, but moving, and there was something about the coins that showed so much life in a place dedicated to the dead. A walking trail circles the memorial and leads to the top of the hill, from which position it is possible to look over the school’s running track and towards the school. On the far side is a small area of reflection where guests can look down on the totality of the memorial or away across a lake and towards the mountains. The power of the space is palpable, and I daresay that it is an appropriately beautiful place for this type of memorial. To that end, and I can’t stress this enough, is that Columbine High School is beautiful. Such is the memory I took away from the school. For all of the footage of the crying and suffering survivors, Columbine in real life is an idyllic place, which somehow makes the massacre so much worse and yet the recovery so much more inspiring. The high school is named after the Colorado blue columbine, the state flower, and the name is fitting. Columbine High School and Clement Park are clearly the flower of this community and you can feel a lot of love walking around the area. Recently, another scholar questioned me about the difference between memorialization and dark tourism, arguing that memorialization is not necessarily completed for the purpose of soliciting visitation and they aren't relatable concepts. I would agree that there are certainly differences needing qualification, as memorials are usually made to honor figures of importance, in this case the victims of a horrible crime, instead of appealing to travelers. But memorials often serve educational purposes as well, and to accomplish that task need to attract viewers. The connection between tourism and pilgrimage is a long-established conception within the social sciences, such that I do not hesitate to argue that tourists and pilgrims are often one and the same. Both tourists and pilgrims seek transformation in some form, often involving themselves in some sort of historical story. In this way, visiting the Columbine Memorial to learn about or remember what happened here is an act of pilgrimage, but one that also satisfies the curiosity of the dark tourist. Yes, gawkers and rubberneckers are frustrating, and Cullen documents that dark tourists descended upon Littleton in the wake of the shooting and continue to plague the town with inappropriate questions, but I suspect from my visit that most visitors are of the far more reflective type seeking to honor and engage more than dominate and violate. Furthermore, I reconfigure the work of art historian W.J.T. Mitchell, who famously questioned What Do Pictures Want? To Mitchell, artworks desire viewership to achieve their purpose. This post-modern anthropomorphizing of inanimate objects may be beyond where most people are willing to go in thinking about art, but serves the purpose of moving the interpretation of art away from the artist’s intention and towards the audience’s consumption of the artwork. In this case, whether memorials are intended for tourists or not, if audiences view them as places of pilgrimage and visitation they become tourist sites all the same. In this way, memorialization becomes transformation and meditation through dark tourism, and one does not preclude the other. Esteemed anthropology Sherry Ortner is famous for chronicling the pathways of anthropological thought throughout the past century. Recently, she argued that anthropology has taken a turn towards ‘dark anthropology’, which she describes as “anthropology that focuses on the harsh dimensions of social life (power, domination, inequality, and oppression), as well as on the subjective experience of these dimensions in the form of depression and hopelessness” (Ortner 2016: 47). Studies of dark tourism seem to fit this bill, as they revolve around places of death and tragedy. But I argue that the study of dark tourism are not dark in nature but actually quite optimistic. Dark tourism itself might be a misnomer for what actually occurs in these spaces, and the study of tourism at these sites may yet prove to be a way for anthropologists to see the light in the darkness. For my part, what I will remember most from my visit to Columbine is not the experience of standing on bloodstained ground, but instead the smiling, waving joggers who warmly greeted me on the walking trails and the students who respectfully stopped at the memorial on their way to other social activities. Much like how I often find inspiration in the strength of the Cambodian people, my Columbine experience was one of life – green grasses, blue skies, and new generations of people that remember the past but are not beholden to it. They are too busy building their present and their future to go backwards. Below is a collection of photographs of the Columbine Memorial that I share without comment (as my words can add nothing to what they represent). But I would finish this post by highlighting one of them, which summarizes so much about what anthropology can learn from dark tourist sites, and what you and I can learn by visiting places like these: ---

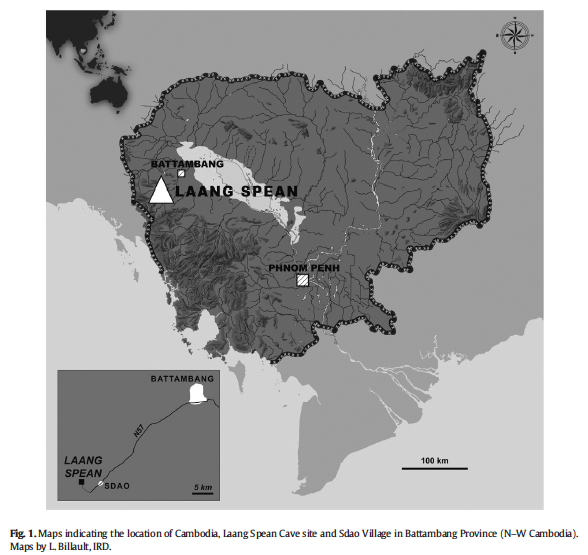

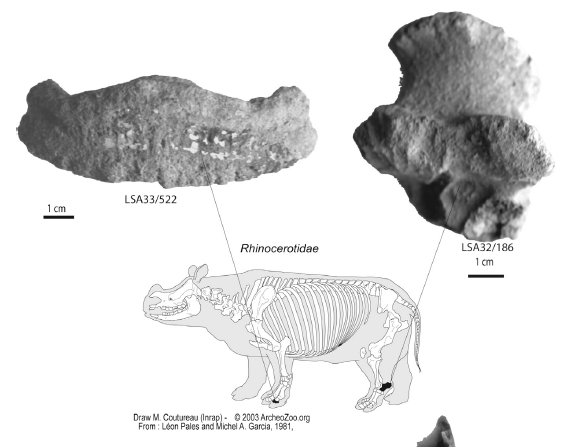

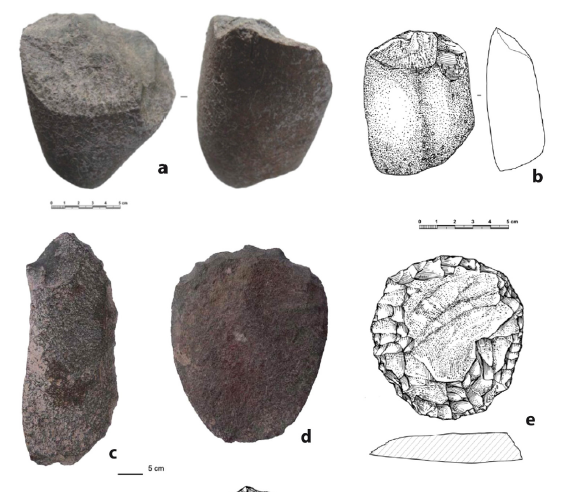

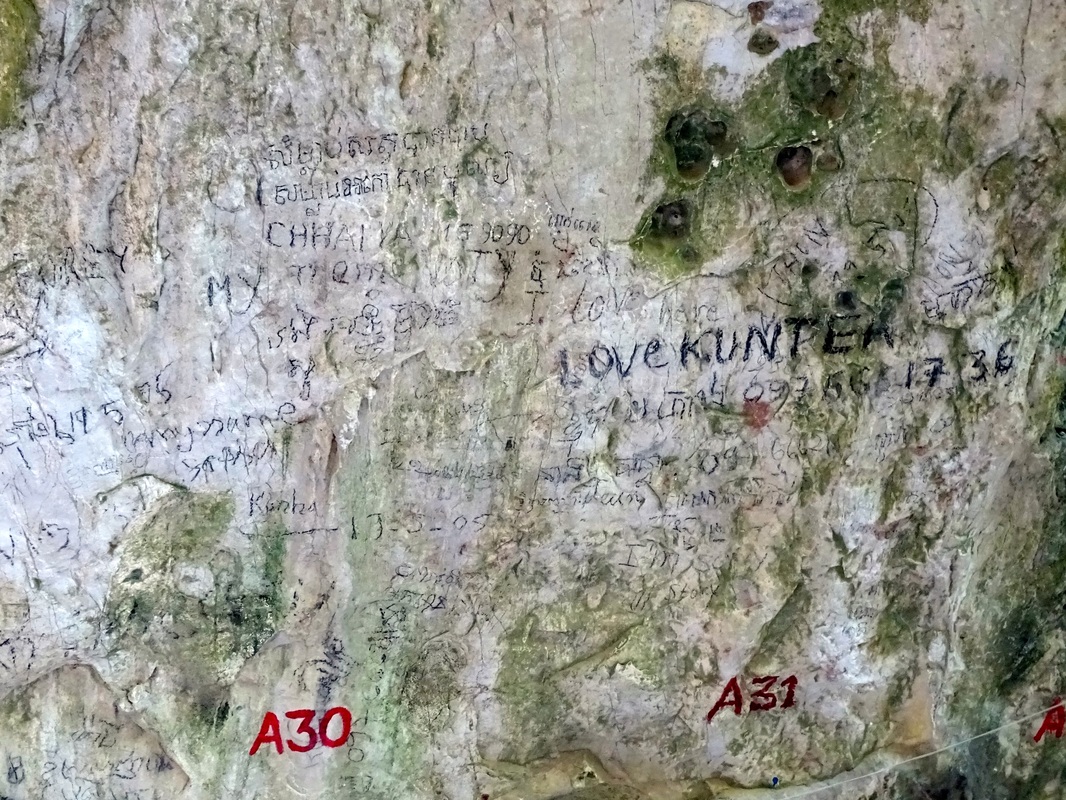

Cullen, Dave. 2016. Columbine. New York: Twelve Publishing. Kelly, Judith. 20 Apr 2019. "I Taught at Columbine. It is Time to Speak My Truth." Buzzfeed News. https://www.buzzfeednews.com/article/judithkelly/opinion-i-taught-at-columbine-it-is-time-to-speak-my-truth Ortner, Sherry. 2016. “Dark anthropology and its others.” Hau: Journal of Ethnographic Theory 6 (1), pp. 47-73. Mitchell, W.J.T. 2005. What Do Pictures Want?: The Lives and Loves of Images. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Sharpley, Richard and Philip R. Stone, eds. 2009. The Darker Side of Travel: The Theory and Practice of Dark Tourism. Bristol: Channel View Publications. Spencer, J. William and Glenn W. Muschert. 2009. “The Contested Meaning of the Crosses at Columbine” American Behavioral Scientist 52 (10), pp. 1371-1386. Strauss, Claudia. 2007. “Blaming for Columbine: Conceptions of Agency in the Contemporary United States.” Current Anthropology 48 (6), pp. 807-832. I’ve wanted to write informal posts about my adventures and ethnographic experiences for a while now, and yet here I am four months into my research with no fieldwork posts to show for it. That changes today, with the first of what I hope will become a series of posts about living and doing ethnography in Cambodia, which I’m not so humbly titling “The Continuing Adventures of Mekong Matty.” Which is a Jungle Cruise reference for you non-Disneylanders, but that’s a topic for another time… I heard about archaeological work at Laang Spean – “The Cave of Bridges” – in the news a few months ago and wanted to arrange a visit. After all, most archaeology in Cambodia is focused on the temples of Angkor, so any significant work being done in Battambang – the focus of my research on tourism – was naturally of personal and professional interest. Luckily, my good friend, Khmer-language buddy, and esteemed archaeologist Dr. Alison Carter knew of a dig at Laang Spean happening from the end of February to the beginning of March. Not only that, but being the amazing person that she is, she knew the head archaeologists – Dr. Hubert Forestier and the (soon-to-be Dr.) Heng Sophady – and put me in direct contact with them. Sophady was eager for visitors and quickly invited me and my research assistant Visal out to Laang Spean in the middle of their dig to see what was going on for ourselves. Laang Spean is easily accessible from Battambang, about 45 minutes by moto down the nicely paved road towards Pailin. Anyone wishing to visit for themselves need only to head towards Phnom Sampeau and keep going past the entrance to that mountain, heading straight to the town of Sdau. Small mountains begin appearing on the otherwise flat landscape near Sdau, and a little beyond the town is a temple near a hill, after which comes a turn-off onto a dirt road that leads towards Laang Spean. This road can be a bit tricky to see at first, but if you travel slowly you’ll notice a sign in French and Khmer that indicates the mountain. From Forestier et al. 2015Then comes the difficult part – actually reaching the mountain of Phnom Teak Trang, where Laang Spean is located. While the highway is easy to traverse, the dirt roads are considerably less so. No signs point the way as you pass through rows of fields growing rice, corn, and other crops, so you may have to stop and ask for directions (although the locals know there’s only one reason for a foreigner to be in those fields, so they’ll point the way quickly enough). Much of the path is pure sand while the rest is mud, so riding a moto can be dangerous and tricky, particularly if there is any recent rain. Worst of all is a hastily constructed wood bridge that you must cross. Visal, being lighter and more experienced with motos than I am, volunteered to take our bike across and I saw several planks of wood lift up on one end where it should have been nailed down. Luckily, we both made it across in one piece. She's a bold kid. A booooold kid.Believe it or not, but this was the easiest part of the road through the field...The Khmer word “phnom” means “mountain,” although in the Cambodian context it’s more like a large hill. In this region, many “phnoms” dot the landscape, so finding the correct one is a bit tricky. The key is to look for the giant scarring cave hole which you can just see about two-thirds of the way up the side of Phnom Teak Trang. The only other indication that we found the right cave was the small collection of motos, tuk-tuks, and beat-up trucks we found at the base – clues that an archaeological team was nearby. It's taller than the perspective on these photos makes it look...A short path through some bushes led to a steep rocky climb up the mountainside. A rope isn’t required, but I still had to stop to catch my balance from time to time for fear of sliding down the loose dirt. I can’t even imagine trying to bring heavy equipment or artifacts up and down this path, and have much respect to those that do. More anthrobutt than you thought you'd see today. Which is odd, since my girlfriend often laments my lack of tushy.The top leveled out into an entrance area of sorts. The cave is exposed to the outside, making it well lit and cool from excellent airflow, and there’s a large foyer-type area on the right before proceeding into the deeper part of the cave to the left. Separating the left and right sections is a tree and collection of vines that hang from the ceiling. A small shrine dedicated to the tiger spirits is located at the bottom of the tree where I later witnessed visiting Cambodian officials (military, political, etc.) pray and burn incense. Buddhist monks also performed a ceremony at this site before the dig to bless the endeavour, as per local custom. The entrance to Laang Spean. "Foyer" to the right, dig site in the back left. "Bridge" all the way in the back.The cave is called Laang Spean – “The Cave of Bridges” – because of several large rock formations that create a bridge-like effect, the largest of which was behind the main dig area. Supposedly there are more than a dozen more caves in the area that archaeologists suspect may house artifacts but are yet unexplored. The cave, while smaller than I expected based on photos I’d seen, was no less beautiful and inspiring. Visal, who loves learning new things about Cambodia that others don’t know, was quite taken with the place and swore to become an archaeologist then and there. Sadly, no one teaches archaeology in Battambang! Behold the Cave of Bridges. Current dig site to the bottom left, the "bridge" in the middle right.About 20 or so Cambodian students from Phnom Penh were digging in the deep test pits, assisted by several French archaeologists with cigarettes dangling from their mouths and two or three foreign volunteers (one American woman was volunteering here before heading to graduate school to study the archaeology of Burma). Visal and I introduced ourselves to Hubert and Sophady, who were kind and enthusiastic about our being there. Sophady was particularly accommodating and carefully guided us around the site answering any questions we had. A shorter man wearing a black shirt and the checkered karma-scarf that most Khmers wear, Sophady is actually finishing his Ph.D. under Hubert and is defending his dissertation on Laang Spean in the next few months (good luck, Sophady!). Based on what I saw in my interactions with him, I have no doubt that he’ll pass with ease and that Cambodian archaeology will be better off for it. Dr. Hubert Forestier and Heng Sophady going all archaeological on me.Between Hubert, Sophady, and some articles I read before visiting the cave, I feel like I now have a decent understanding of the history of the cave, although I’m not an archaeologist (so, digger friends, go easy on me if I sound like an idiot). The first archaeology in the cave was performed in 1965 by French couple Cécile and Roland Mourer, who found a flint point before performing further research. Over several years of work, the Mourers found pottery, bones, molluscs, stone tools, animal remains (including a rhinoceros!), and a variety of other data that indicated significant prehistoric usage of the site. In 1970, they wrote that “to our knowledge, [Laang Spean is] the first prehistoric cave deposit reported in Cambodia” (Mourer 1970). Not only that, but they also mentioned a long history of habitation by hermits and religious devotees, signifying the continuing importance of the cave to the locals even today. From Forestier et al. 2015Unfortunately, and you had to know this was coming, the Mourers were forced to abandon their research and flee the country with the rise of the Khmer Rouge. According to Sophady, research was not fully revived at Laang Spean until about 2009, when he and Hubert from the Franco-Cambodian Prehistoric Mission received funding to continue the work that the Mourers started. As Sophady described it, there are lifetimes of work left to be done that will require many more decades to complete, which is both exciting and daunting. Deep pit = long history (most of the time)Nevertheless, in the short time that archaeologists have been working there, Laang Spean has revealed a fascinating history for the habitation of the region. According to Sophady, the test pits reveal three distinct layers in the limestone, indicating three major time periods of occupation – a Neolithic layer (for lack of a better term), a Hoabinhian layer, and an ancient pre-Hoabinhian layer dating back tens of thousands of years. The stone tools mentioned above, which they continue to find (and which they let Visal hold and inspect, to her astonishment), are indicative of the Hoabinhian cultural complex. The Hoabinhian people (named after the town in northern Vietnam in which the first materials were found) are known for specific tool-making techniques as well as certain dietary preferences, which includes seafood (hence the molluscs found on the top of the mountain). Sophady estimates that the Hoabinhian people who lived in this cave probably did so somewhere between 9000 to 3000 years ago. From Forestier et al. 2015Five burials have also been found – four men and one woman dating to between 1,700 and 1,300 B.C. Some burials were adorned with bangles and gifts, while others were left bare, leading the archaeologists to propose that the society occupying the cave had some form of social hierarchy. They also found 2,700 stone beads, from which later research may discover trade networks with other groups around Asia. Sophady suspects there are more burials left to uncover in the future. Photo of one of the burials before it was excavated. Notice the bangles on the wrists.The burials are likely from the Neolithic period, although the term Neolithic is highly problematic and hard to define out of context. This problem is made more complicated because the different layers of occupation are mixed together a bit nearer the surface, making exact dating and separation more challenging. According to Sophady, the important thing to know is that the occupants of the cave changed at some point in history. Whereas some occupants used the cave to bury their dead, likely indicating a certain reverence for the site (and perhaps involving some form of spiritual belief), later treated the cave as a mundane living space. Thus, the common-day remains of a living people – seafood shells, food refuse, etc. – have disturbed the pristine burials underneath. The difference in usage of the cave has implications for the shifting cultural importance of the site over time, and is something the archaeologists hope to clarify more in the future. The oldest layer is not yet fully explored, although the data indicate that some form of occupation may have occurred in the cave as far back as 71,000 years ago. Hubert and Sophady were quite enthusiastic about the prospect of further research into the deeper and older layer, as there’s potential for the information gained to rewrite the history of human occupation in Southeast Asia. Local students and foreign archaeologists all working together...for science!Unfortunately, Laang Spean is threatened by the encroachment of business development. According to Sophady, the cave is not currently protected as a research site and he’s worried about a Chinese company that has been buying up nearby mountains and caves to exploit the limestone found within in order to make cement. When I asked about UNESCO protection, Sophady shrugged off the site as being “too small” to request such a thing, and thus he’s relying on media attention influencing local politicians to protect the site. From my observations, the campaign is working so far. After a few hours, several well-dressed Cambodian officials came to visit the site, including the local chief of police and an assistant to the Governor of Battambang Province. With their arrival, Sophady called off the student workers, who proceeded to set up a large tarp on the rocky and root-filled ground in the “foyer” area while the archaeological administrators took the officials on a tour. Eventually, everyone sat down on the tarp for a communal lunch prepared by women from the local village. "Hey, I just met you, and this is crazy, but here's a camera, so let's take selfies..." |

AuthorMatthew J. Trew Archives

April 2019

Categories

All

View Disclaimer and Terms of Use |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed