|

Greetings once again, friends and fellow adventurers! After several years away, I’ve finally decided to revamp this website and start writing again. Apologies for being away so long, but life has been a bit of a roller coaster the past two years or so and I’m only now starting to settle down and let my head clear. I’ve cleaned up some of the past postings, so for the few of you who actually missed reading my thoughts and musings, please bear with me for a little while as I try to get this site going again and re-fill the content. I wish I had a better occasion for my return but, honestly, I decided to write again because today is the 20th anniversary of the massacre at Columbine High School – an event that deeply affected me when I was younger, as I’m sure it did you. Normally, I wouldn’t comment on this event, but I was actually in the Denver area last month and decided to visit Columbine High School and the memorial they’ve established to the events of two decades ago, so I thought it might be an interesting way to merge my personal interests with my professional life to briefly remark on that experience and what I find to be the more optimistic aspects of dark tourism, a term you may be familiar with thanks to a recent Netflix show on the subject (which I do NOT recommend). I’m not going to rehash the entire tragedy, which is well known to most people of my generation, because it would seem exploitative and impossible given its complexity. I have no connection to the event and no real right to it, as I was living almost 1,800 miles away on the South Carolina coast at the time. I will say that, when I knew I would be in the Denver area for work and decided to visit Columbine High, I bought and read the book Columbine by Dave Cullen, who was one of the journalists actually on the scene twenty years ago. I recommend the book if you are interested in this event and want a fair accounting of what happened along with thoughtful questions about our communal misunderstandings of the tragedy, as well as some insightful commentary about what has happened in that community more recently. Cullen has some controversial viewpoints and I can’t claim to agree with everything he says – for example, I find him conflicting in how he ascribes the violence purely to psychopathy, and yet struggles to resolve this perspective with respect to the offenders’ social network – but I am convinced by several of his most important points. According to Cullen:

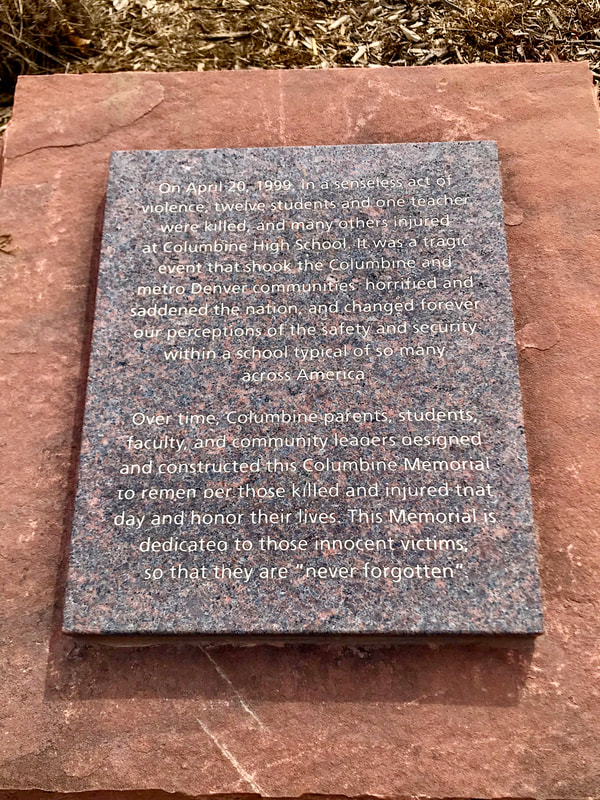

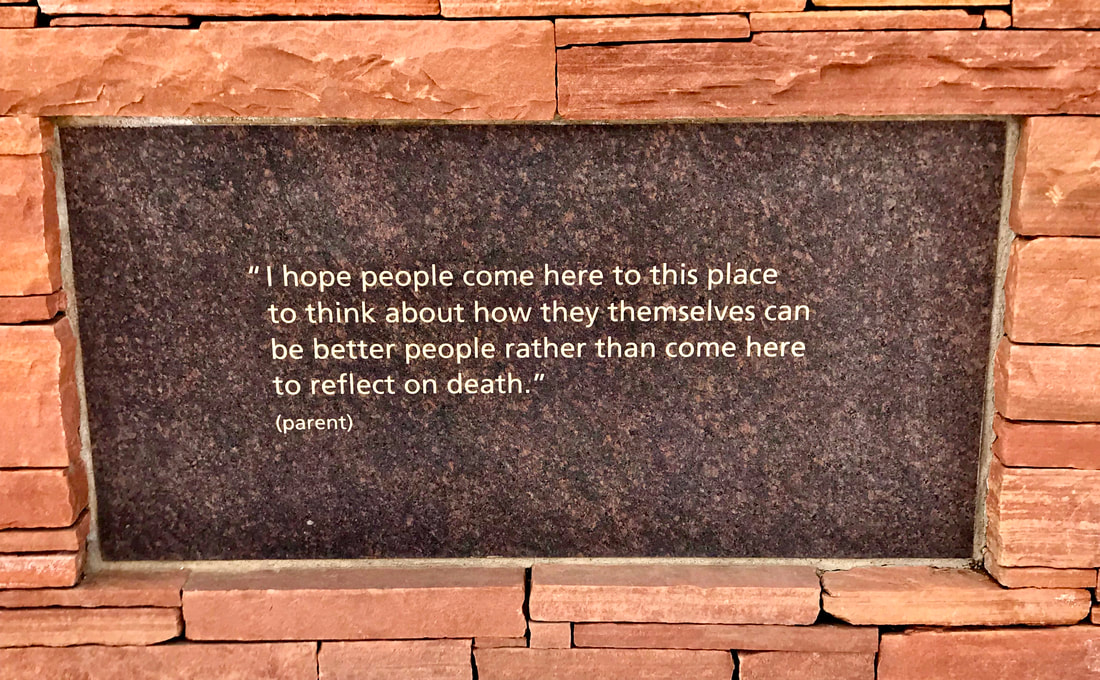

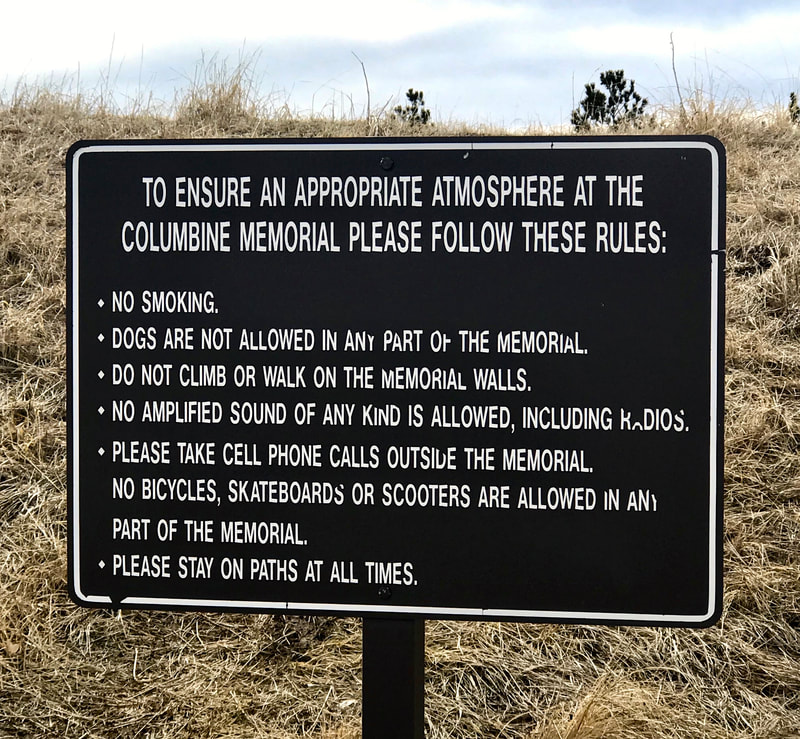

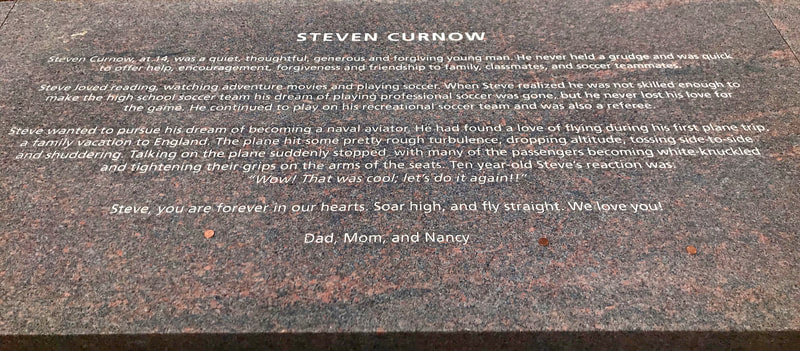

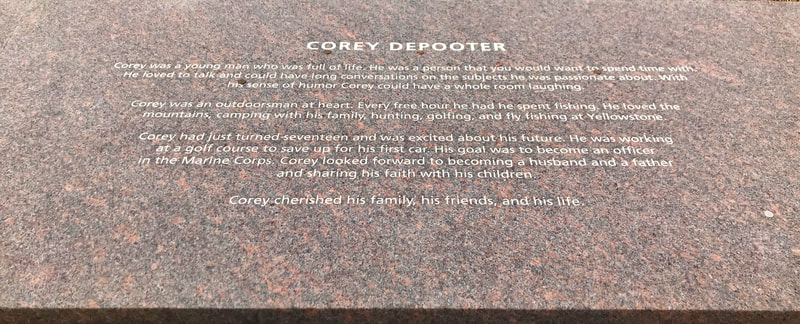

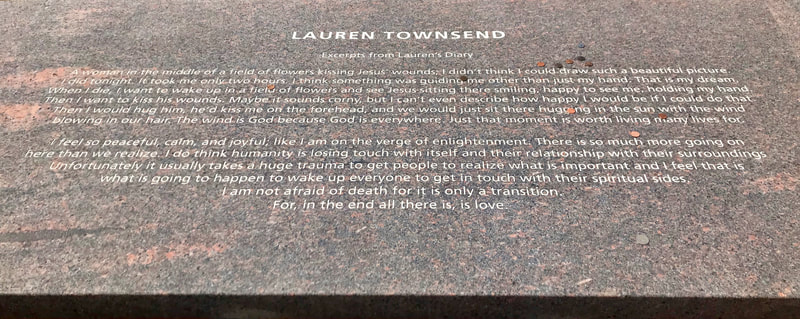

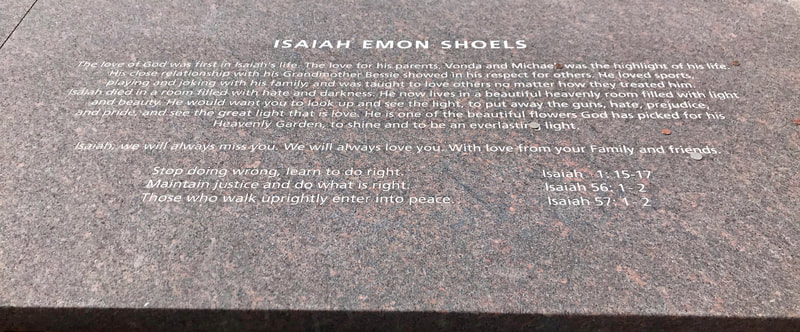

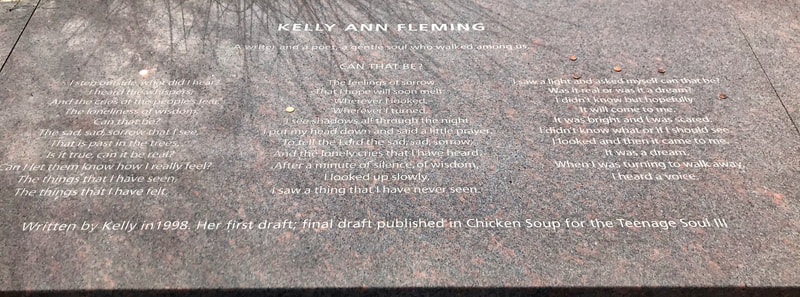

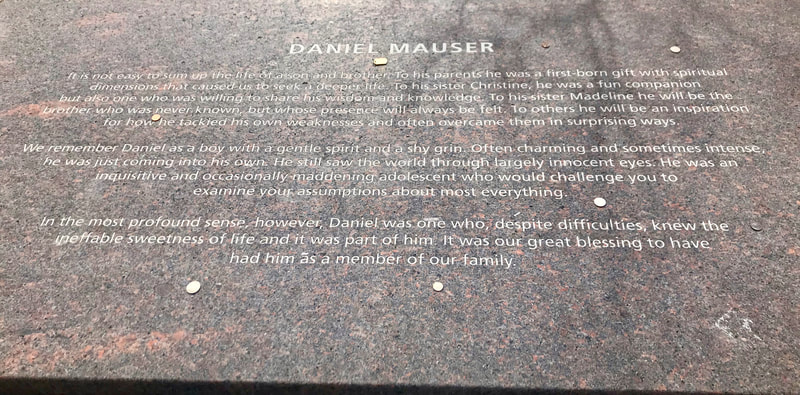

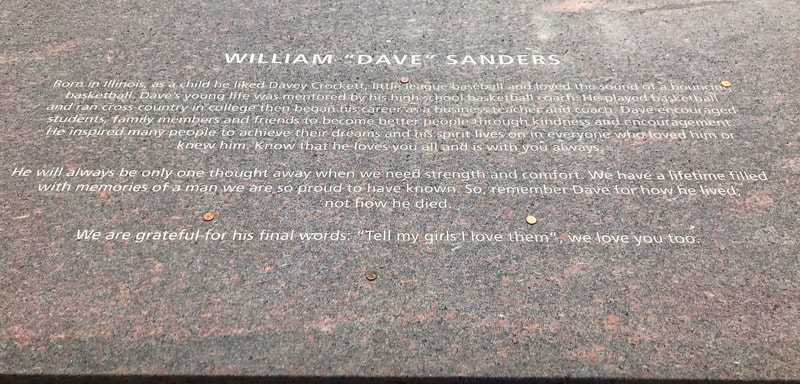

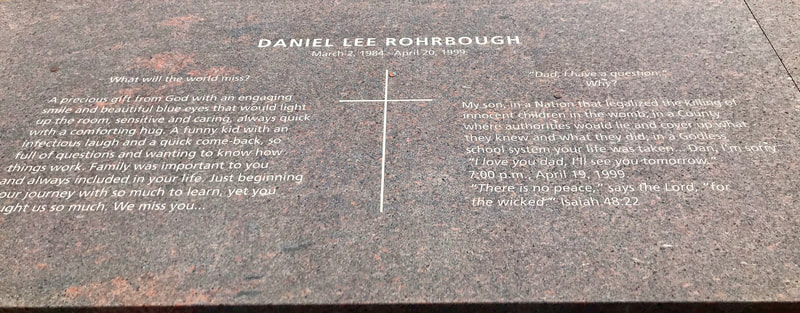

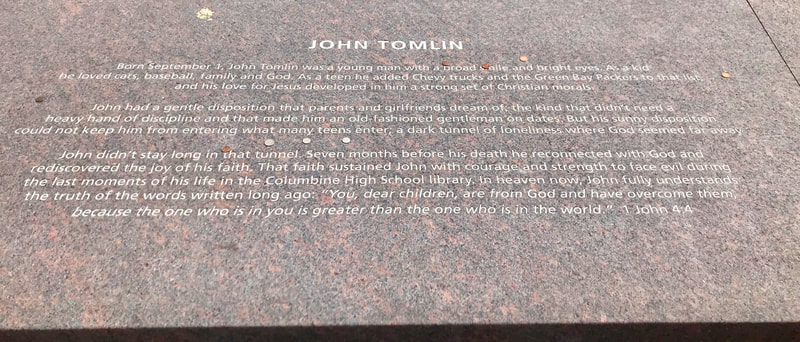

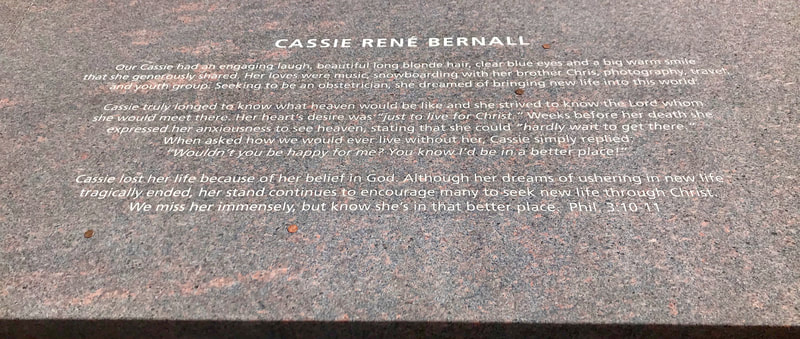

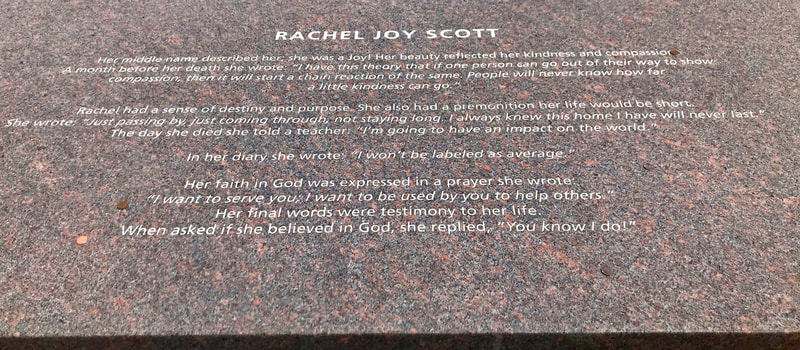

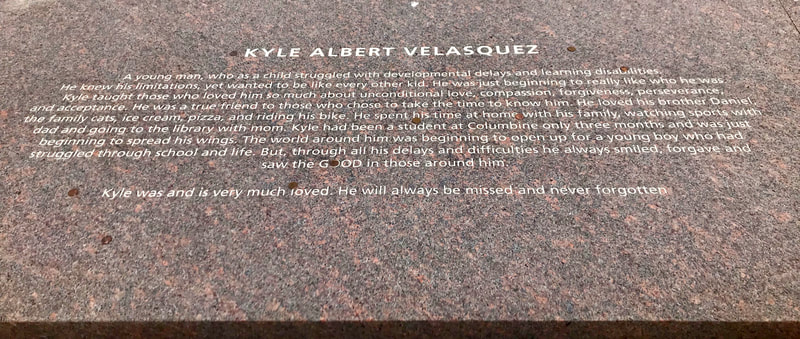

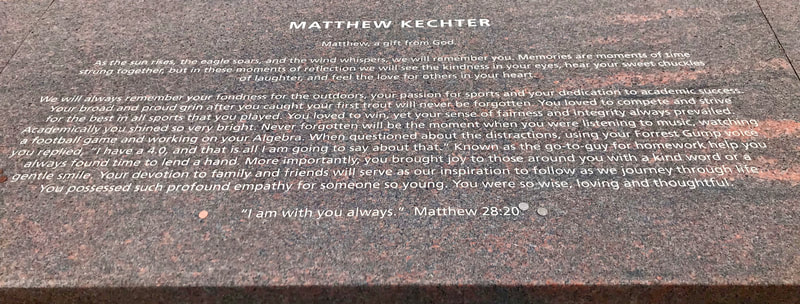

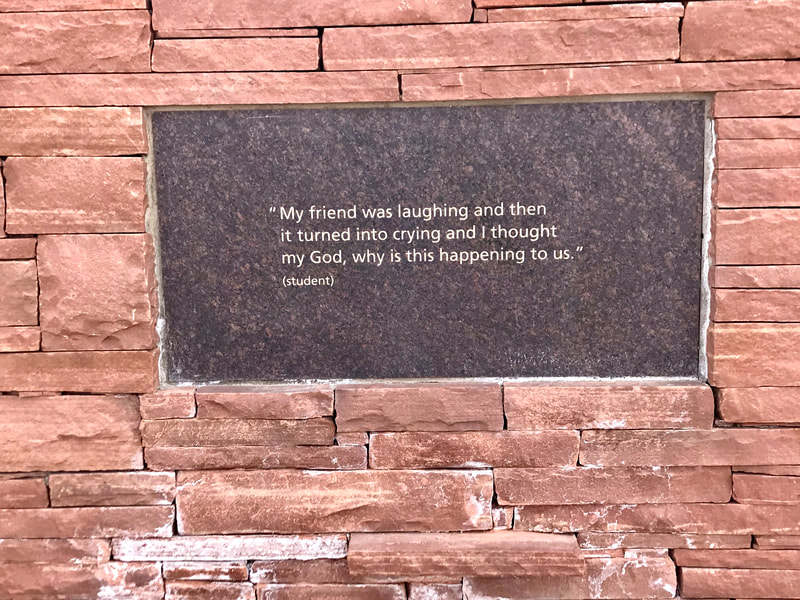

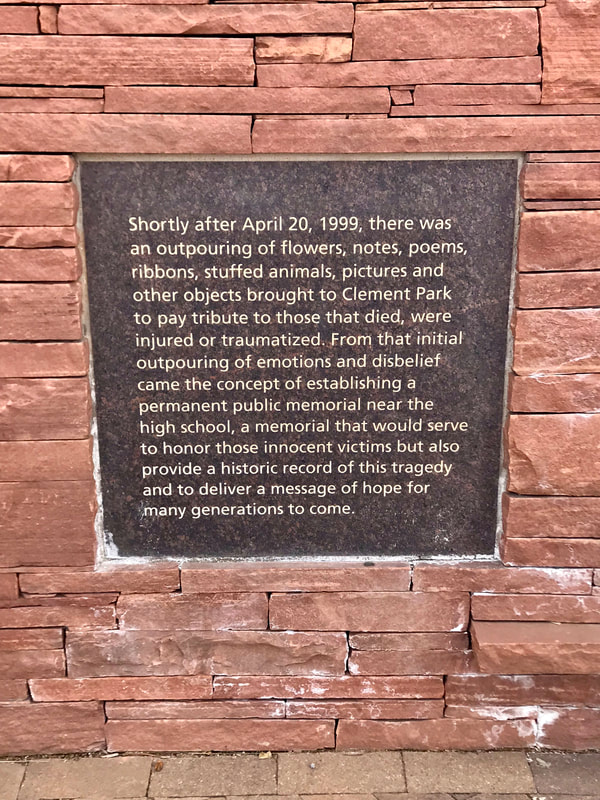

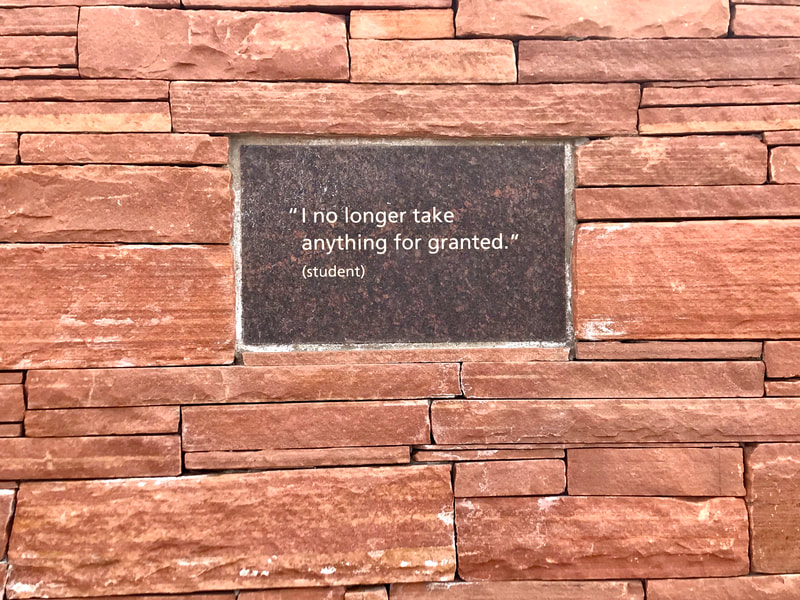

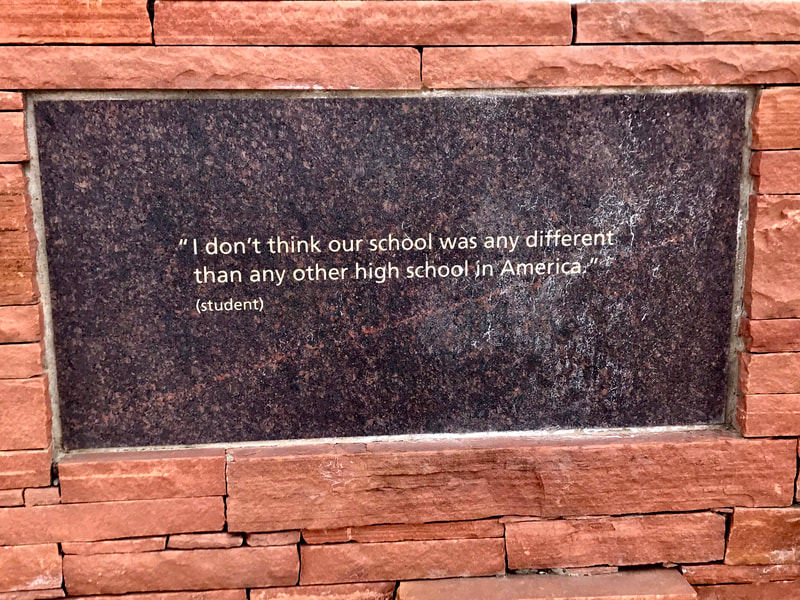

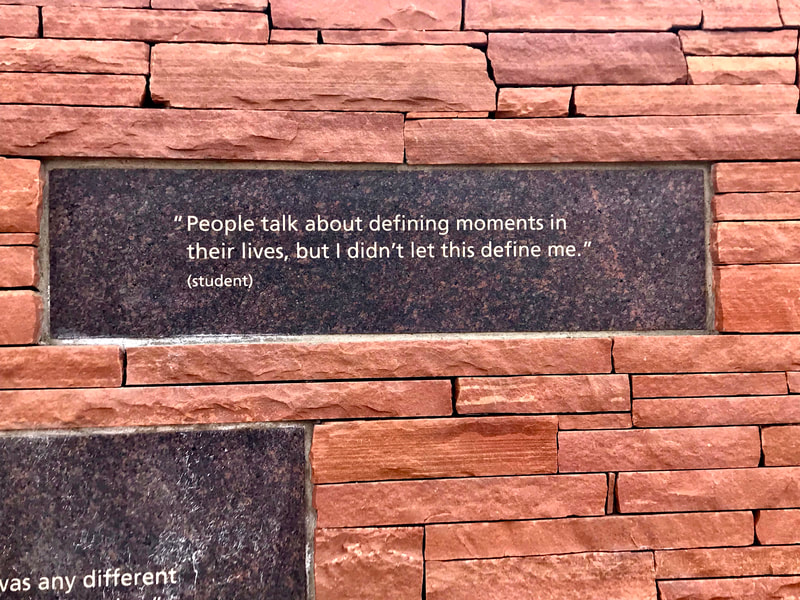

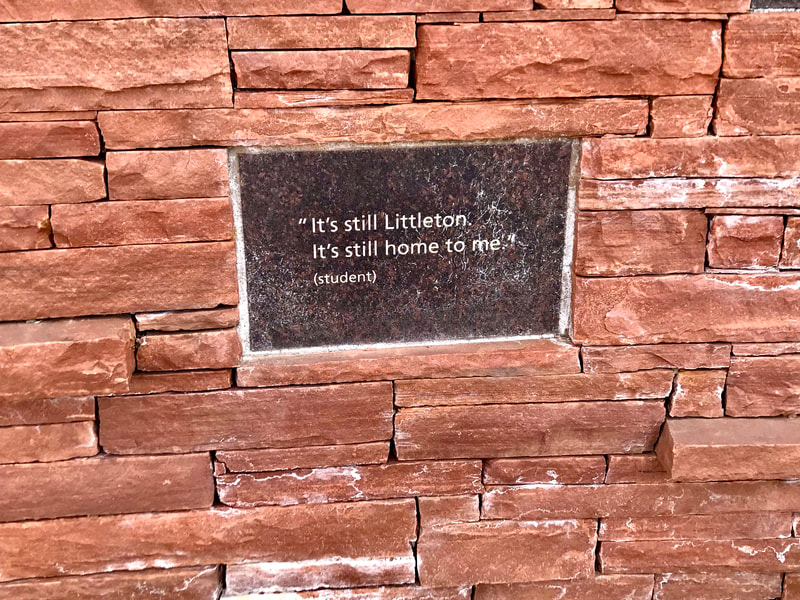

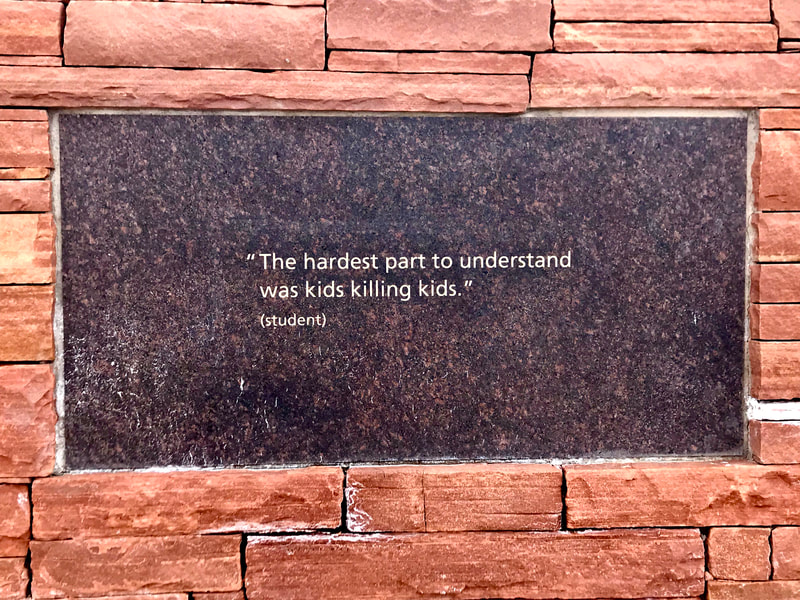

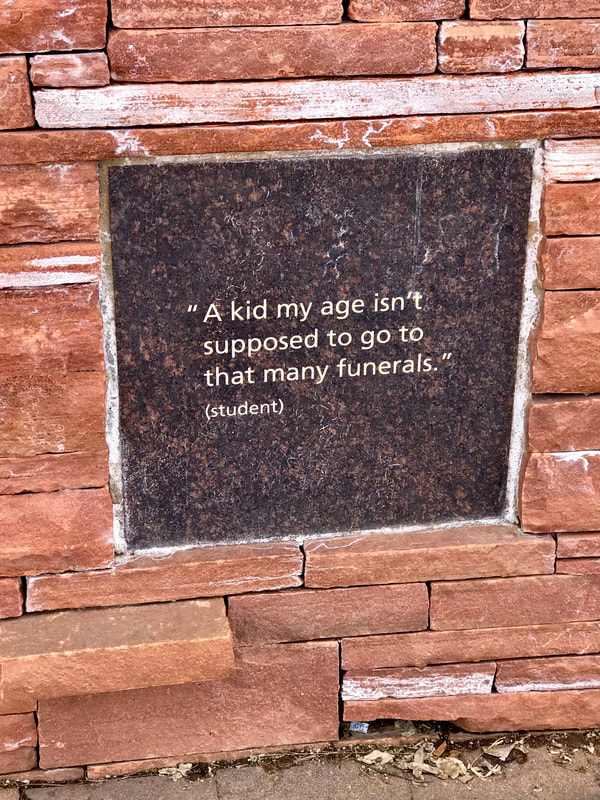

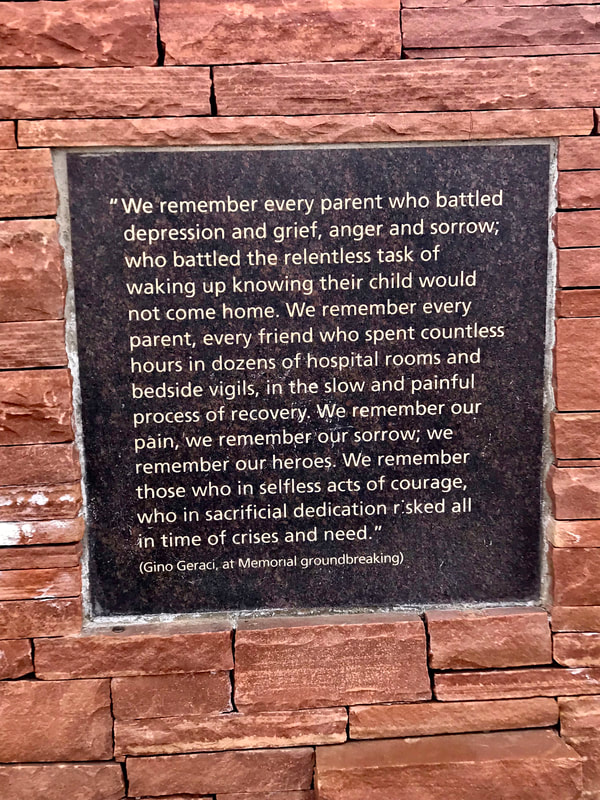

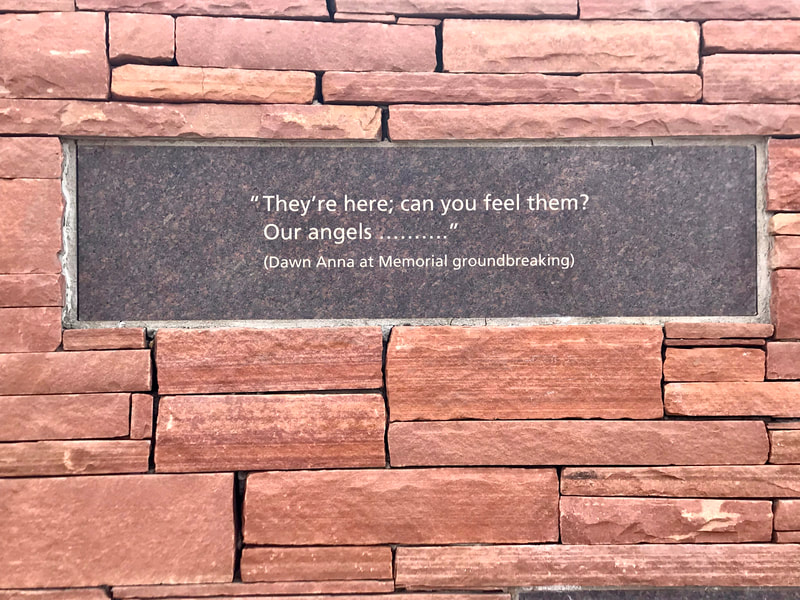

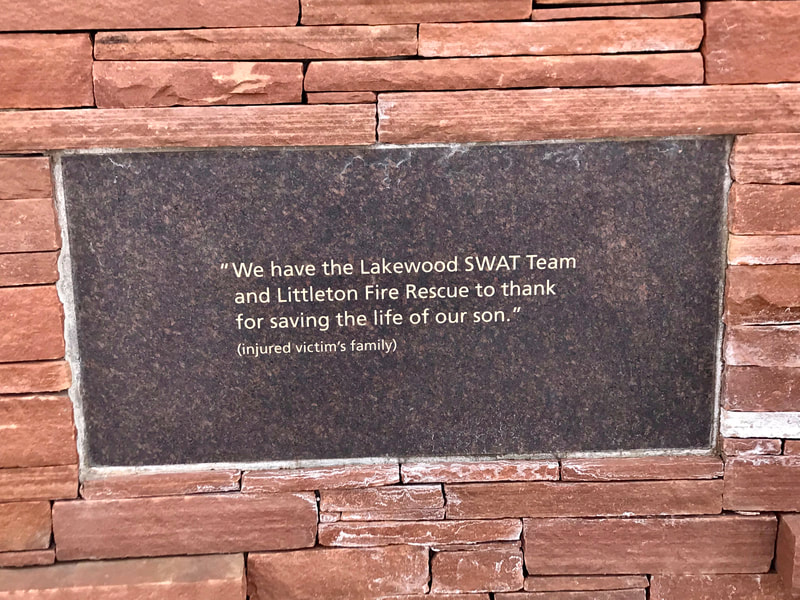

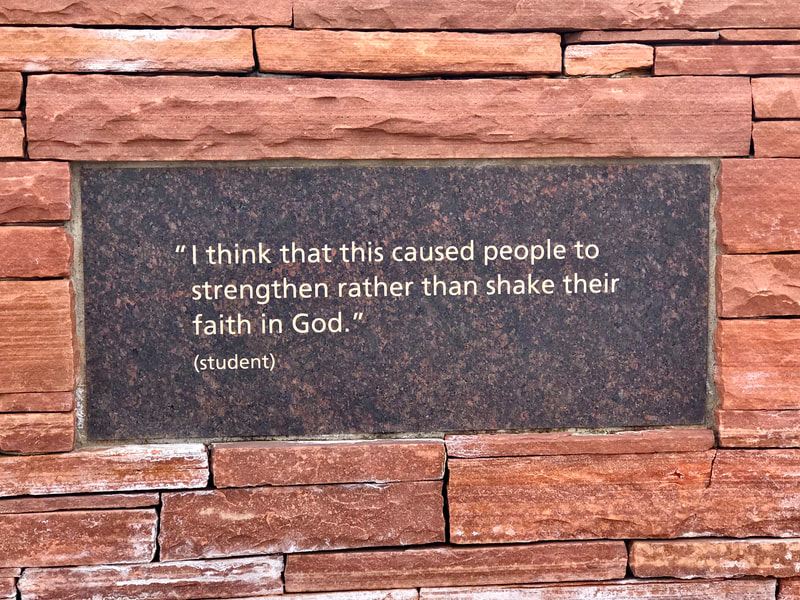

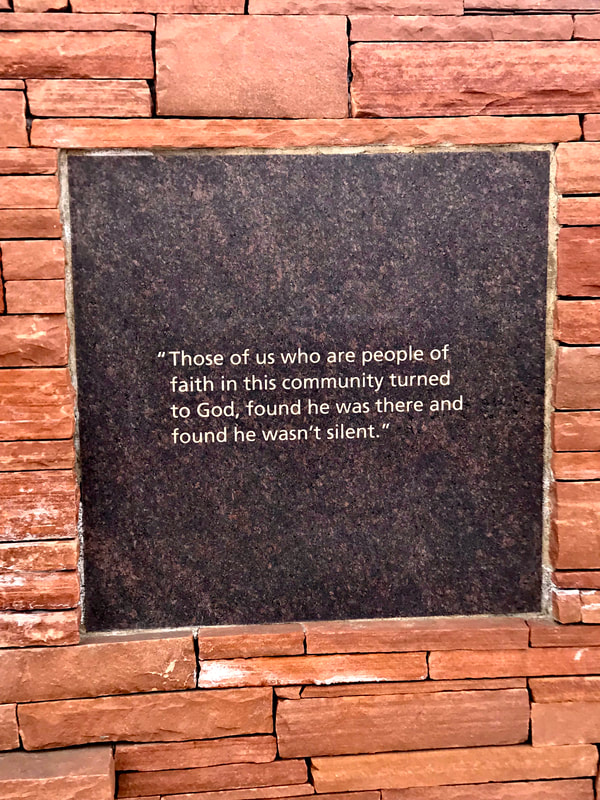

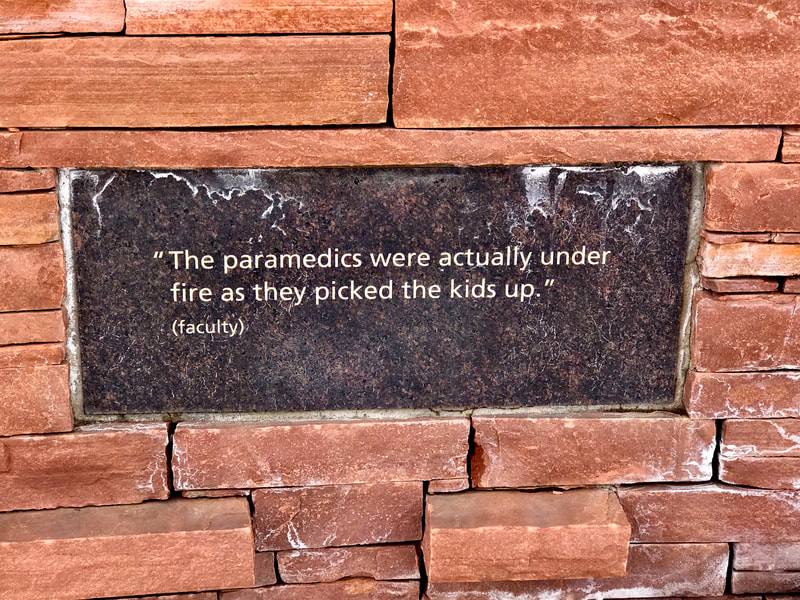

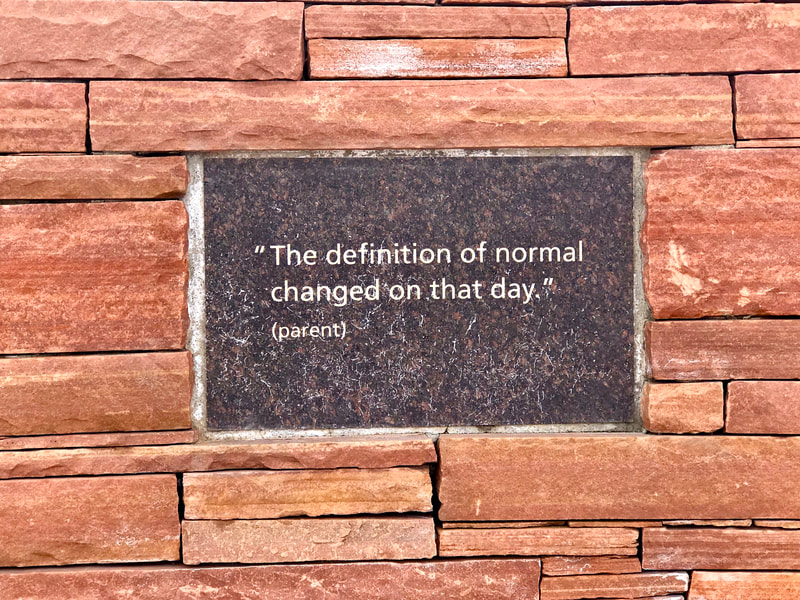

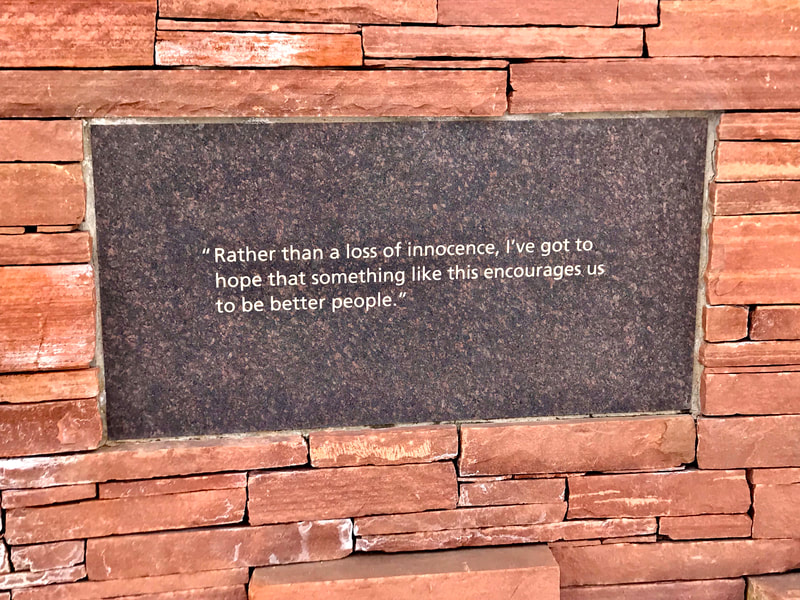

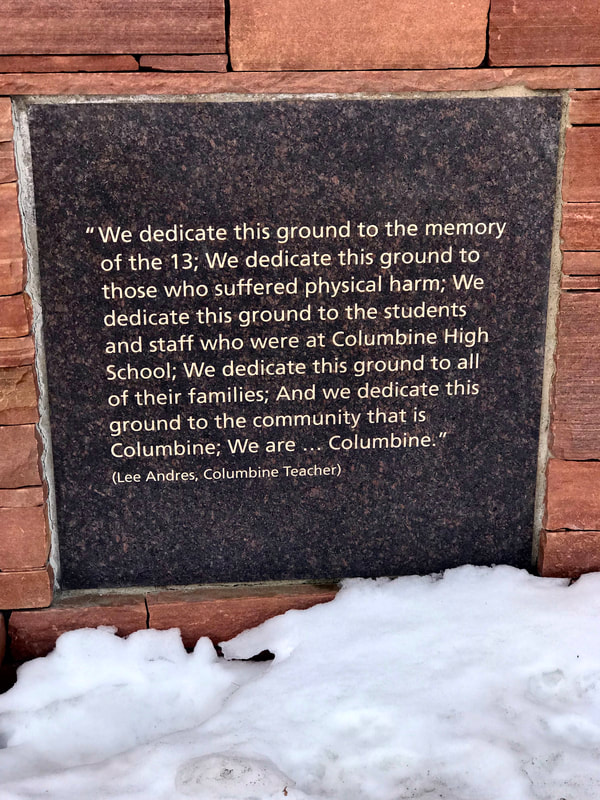

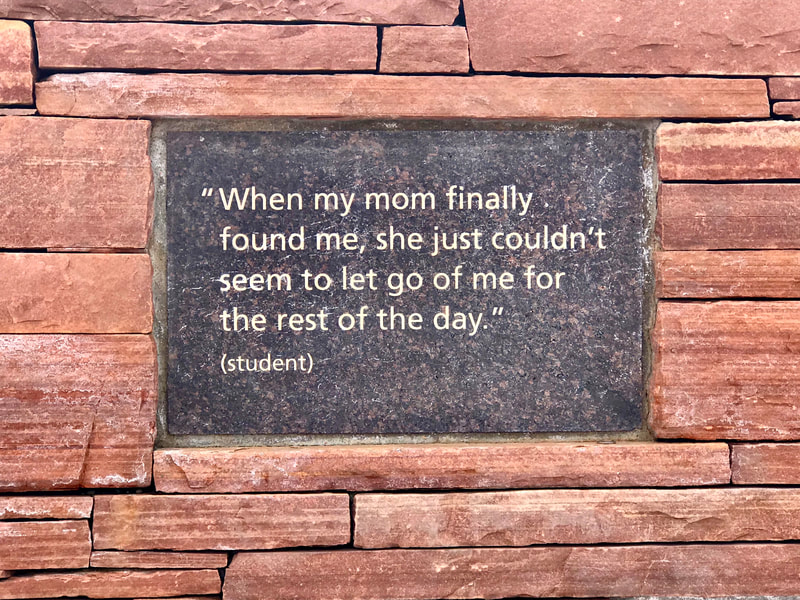

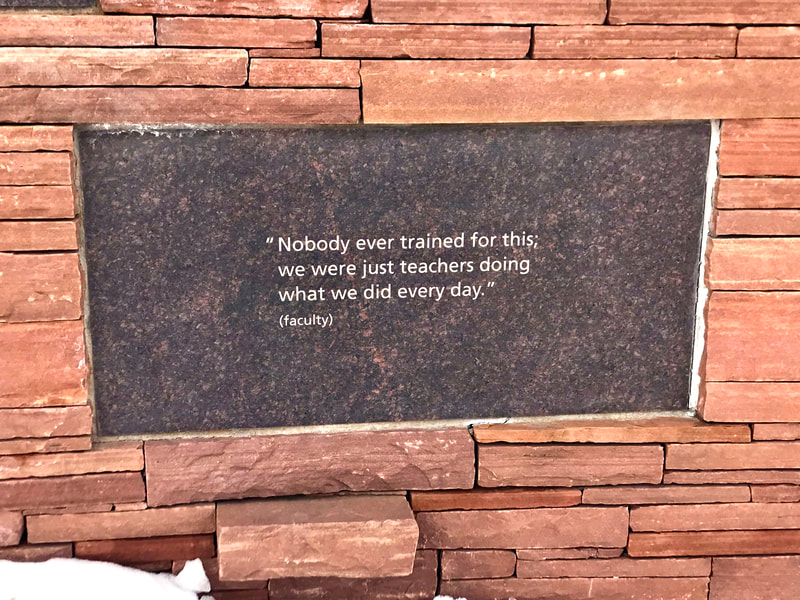

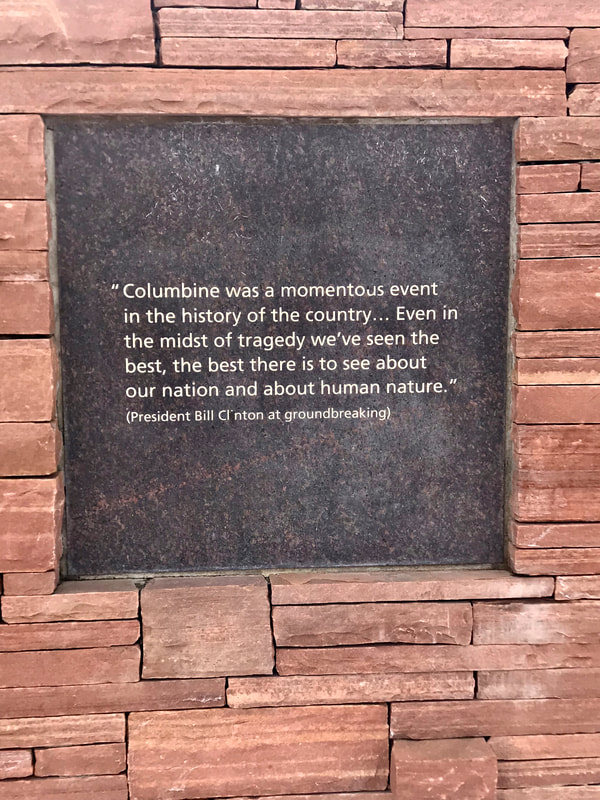

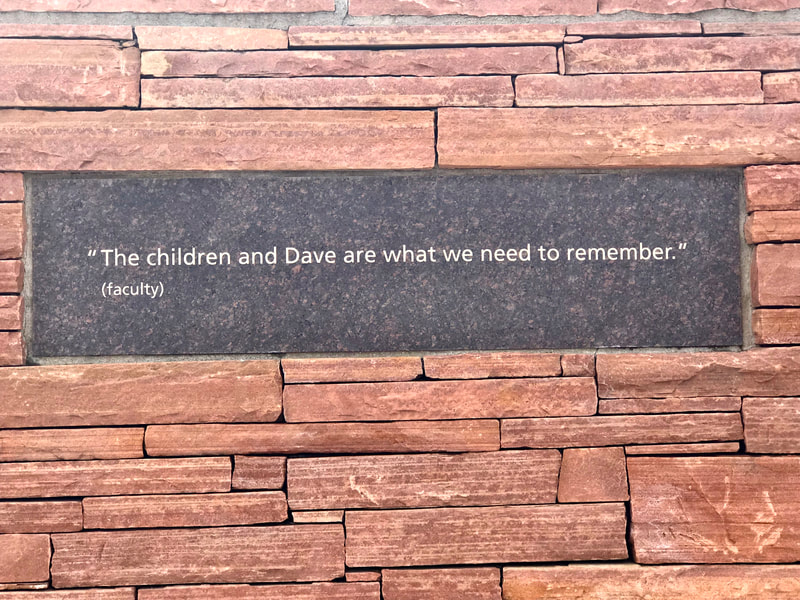

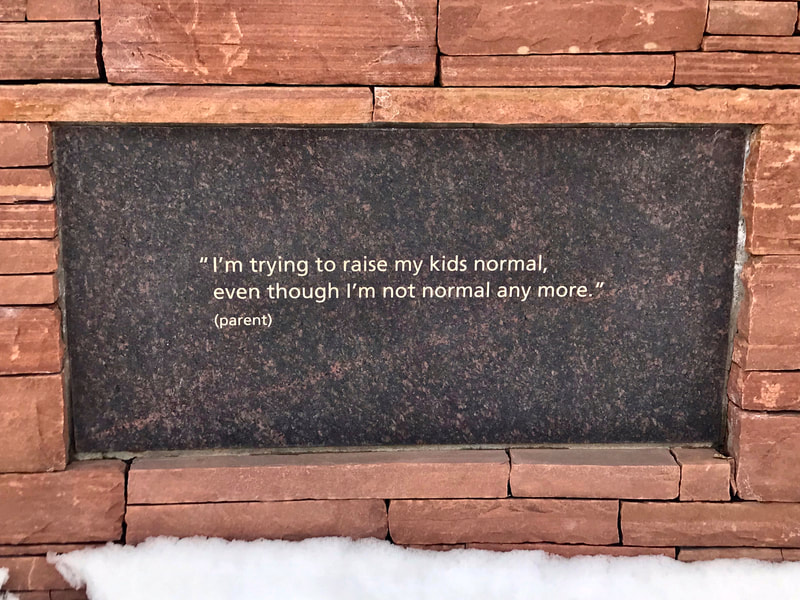

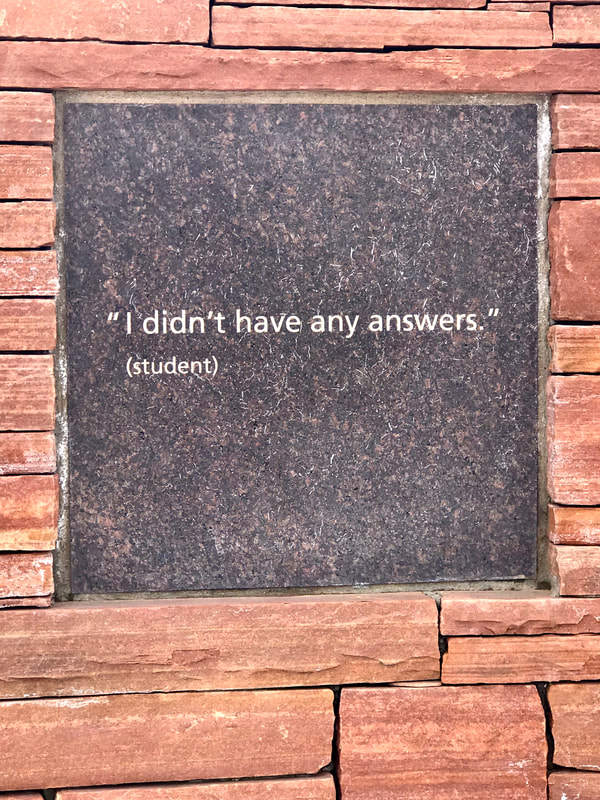

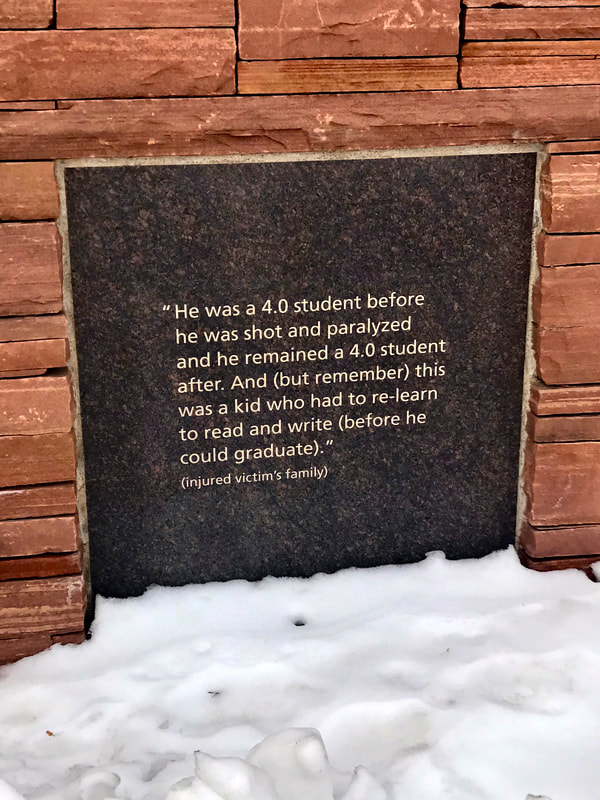

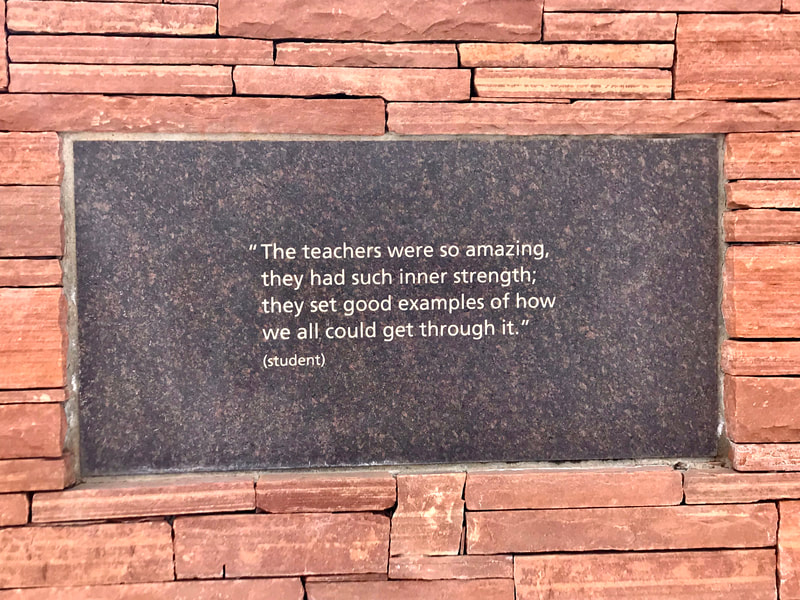

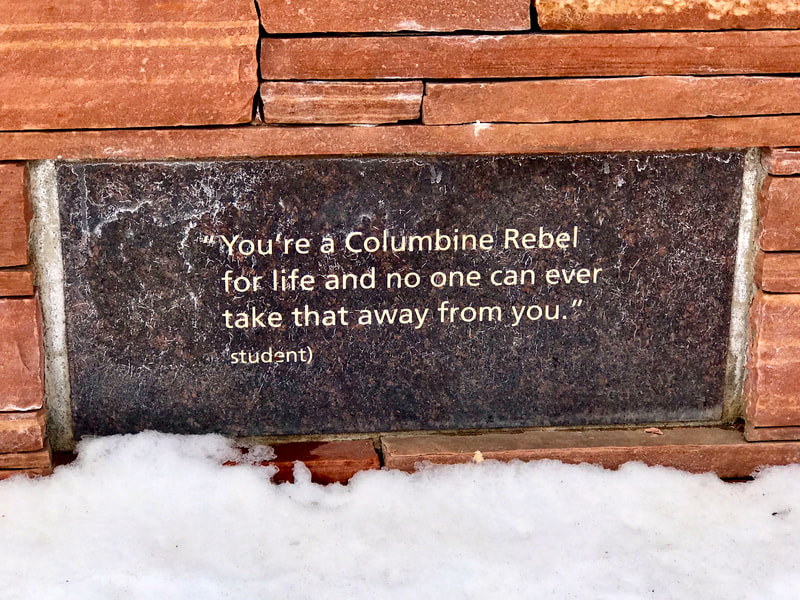

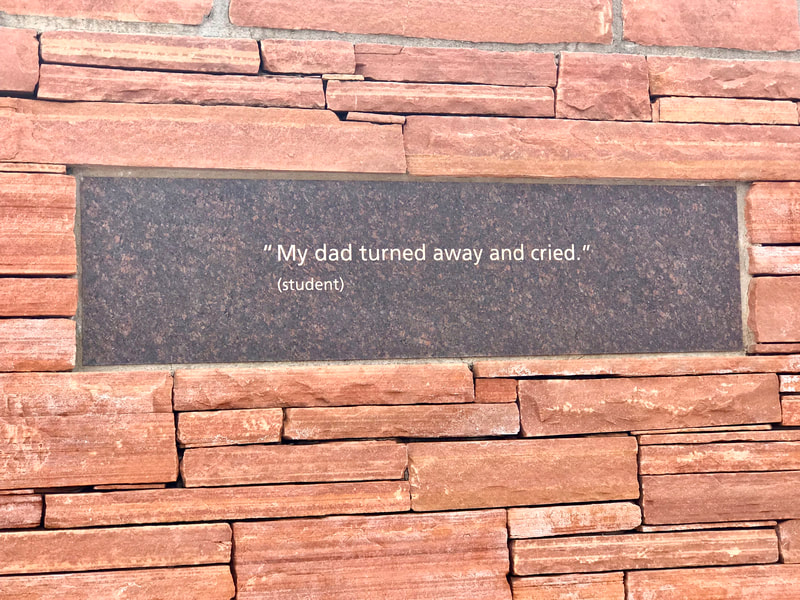

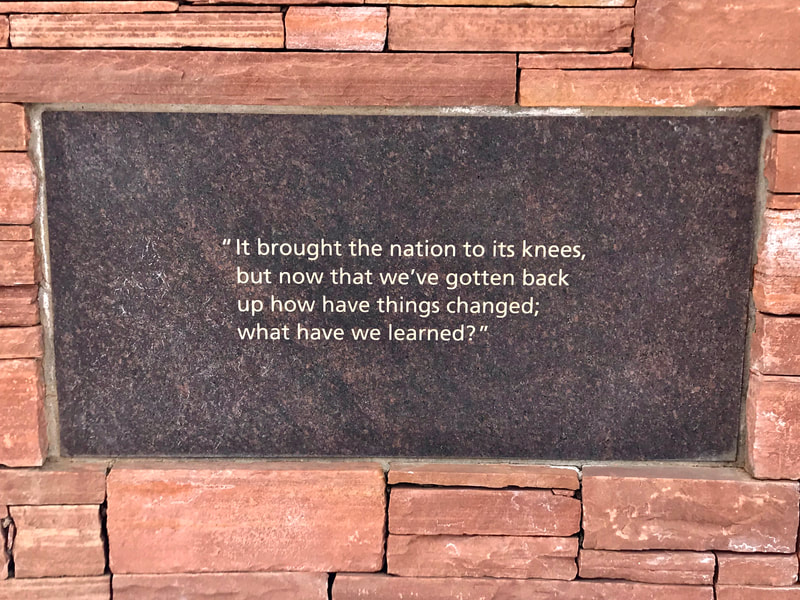

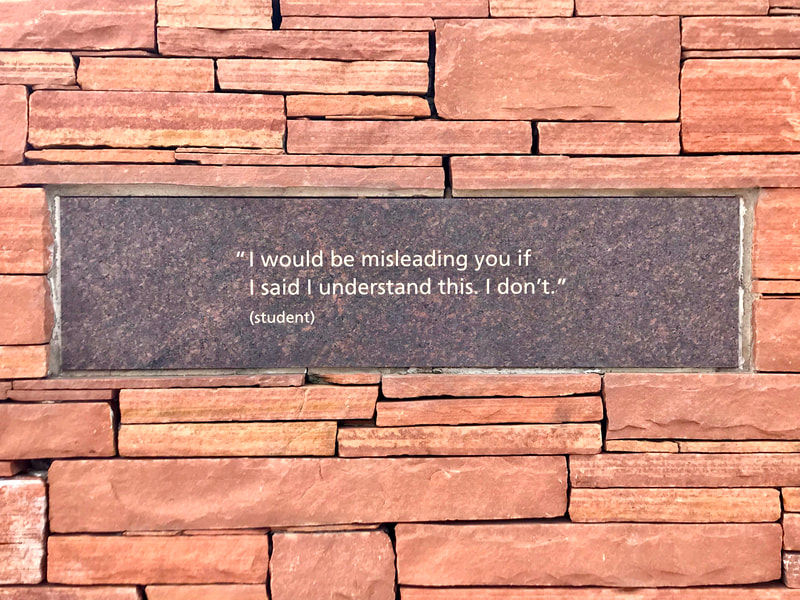

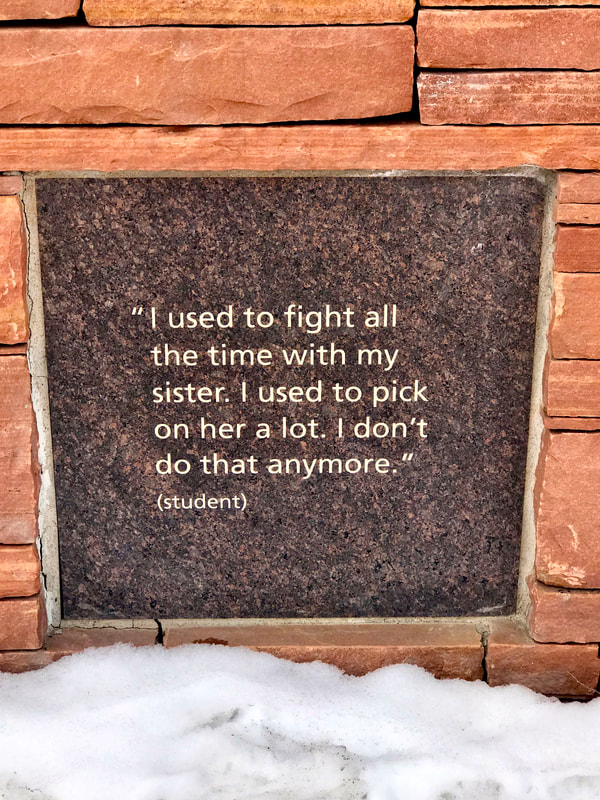

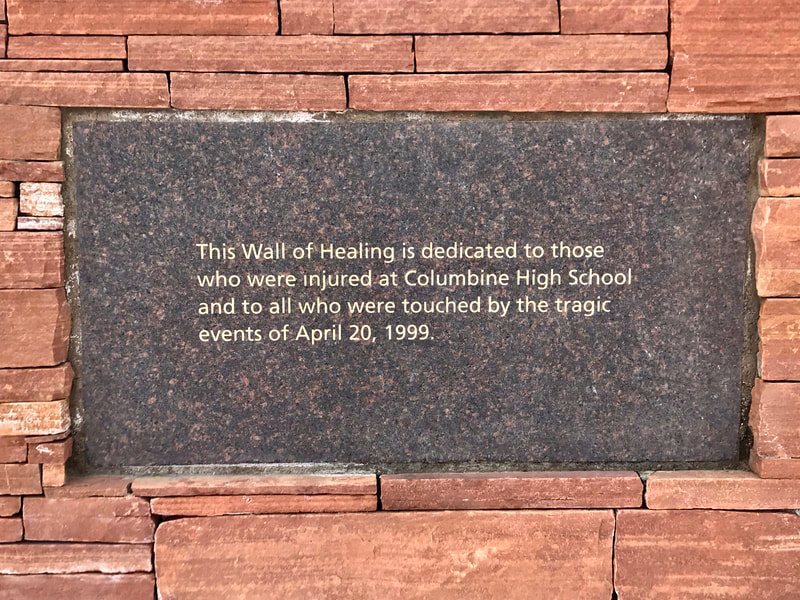

From an anthropological standpoint, I see Columbine as an example of how communities come together even in the darkest of circumstances. My specific focus in anthropology returns to this theme in numerous ways, as I am a specialist on Cambodia, which endured a genocide in the 1970s that resulted in millions of deaths, as well as someone who studies dark tourism, which Professor of Tourism and Development at the University of Central Lancashire Richard Sharpley describes as “travel…towards sites, attractions or events that are linked in one way or another with death, suffering, violence or disaster” (Sharpley 2009: 2). In my capacity as a researcher, and as someone with an interest in the human experience at such sites, I have visited numerous places of death, from serious to humorous – for example, the mass graves of Chhoung Ek, commonly known as The Killing Fields, in Phnom Penh, Cambodia; Wounded Knee on the Pine Ridge Reservation where American troops slaughtered hundreds of Native Americans, mostly unarmed women, children, and old men; the cemetery of Key West, Florida, where graves from the USS Maine are buried near the remains of former slaves and others who died in the Jim Crow era (plus a famous tombstone that reads “I told you I was sick!”); the grave of Martin Luther King, Jr., outside the Ebenezer Baptist Church where you can sit in a pew and listen to recordings of his sermons; Mount Moriah Cemetery in Deadwood, South Dakota, where colorful characters like Wild Bill Hickok and Calamity Jane are buried; the Winchester Mansion in San Jose, California, which is supposedly the 'most haunted house in America'; and so on. From ghost tours to memorials to great tragedy, I try to run the gamut of the dark tourist experience whenever possible. My approach towards going to these places is rather Zen-like: you must experience them with an open heart and open mind, accepting your feelings in full whatever they may be and then letting them go when it is their time to leave. In this way, you appreciate what the experience teaches you and carry forth the lessons therein but also recognize that tears – of which there are many – need not be permanent. I often find that tears, smiles, and even joyous laughter are not mutually exclusive even in these places of death, and there's something deeply uplifting about crying your heart out only to smile and even laugh at the smallest of silver linings in a place that might otherwise appear to have none. Such experiences are cleansing. Sometimes it’s good to feel bad, to lose your mind to your grief temporarily, and to then realize that you can put yourself back together again. My desire to visit Columbine was certainly motivated in part by my desire to confront and reframe my emotions about the massacre, which I consider a seminal event from my childhood that I care about far more than most other tragedies (not to sound callous or anything), and the visit absolutely accomplished those aims. Like many others, I hold am fascinated by tragic events, especially cult-like activities such as Jonestown and Waco, which I think are feelings that stem from a natural human curiosity about the extreme behavior of others. There's also a sympathy there, and I often find myself empathizing with victims and perpetrators alike as there are usually social factors in their decision making that are familiar to my own experience, even if we made radically different decisions along the way. Even with Columbine, I find myself rejecting the labels of inhumanity placed on the shooters because what they did, depressing or not, was an extremely human act with deeply human consequences. Although not a cult, Columbine is a moment that created a community more than destroyed it, and I find myself attracted to such a powerful magnet of human adaptability. Columbine is in the town of Littleton a few miles south of Denver, Colorado, with the Rocky Mountains looming in the background as they tend to do in this region. I find it interesting that the details we miss in video footage of tragic events like Columbine are usually the things we focus on in person. For example, to me the news footage of the massacre at Columbine makes the school seem almost secluded. We see students running from the building through large grassy fields, exposed to occasional gunfire from the upper story windows. This grassy area is Clement Park and does indeed surround the school with lots of green, but on the other side of the school are residential areas that push right up to the school grounds. It’s actually quite a busy street that passes by the front of the school, with lots of activity from cars and pedestrians. And, of course, since most news footage is shot from the top down perspective of people in helicopters, we lose the perspective of the Rocky Mountains, which are visible from a hill near the school and provide a gorgeous backdrop. In many ways, I think Columbine High School is one of the prettiest school campuses I’ve ever seen, as many of the classrooms face the mountains – far better than the parking lot I used to stare at during math class. Clement Park, where most of the survivors fled, is an active recreational center with sports fields and walking trails. Even on the cold day in early spring when I visited, the park was quite busy with visitors. Families were picnicking, the fields were being prepared for baseball games and other sports, and lots of runners and walkers were using the trails – including a large number of older couples, which added a sense of gentility to the place. Unlike other memorial sites that I’ve visited, Clement Park in no way felt like a place of sadness. Yes, many people stopped near the Columbine Memorial to respectfully read the inscription or take a moment of reflection, but the general mood was jovial. This park is the beating heart of the community, and it showed. At the top of a tall hill – the same hill, in fact, where the crosses were once placed – is the Columbine Memorial, the official monument to the tragedy. Access is open to all visitors, although park signs are placed around the memorial instructing people on proper behavior – no loud music or cell phone usage within the memorial space, for example. The memorial is carved out of the backside of the hill such that when you are viewing the memorial itself, you cannot actually see Columbine High School. The intention seems to be that your focus in this moment should be on the individualities of the victims, not on the broader presence of the school or the sensationalized details of its spatial history. In this area is an inner circle consisting of a ring of thirteen plaques for each of the victims, adorned with a personalized inscription by their families. Cullen provides a wonderful discussion of the politics of these inscriptions in his book, again showing that something so seemingly simple as memorializing the dead is anything but easy. The ground is inlaid with the form of a large memorial ribbon with a heart shape at the top, and fountains are nearby for aesthetic effect (though they were turned off during our visit due to the cold). An exterior wall includes numerous plaques with quotes from the community, praising the efforts of first responders and urging people to remember what happened here. The design is well-conceived, as the words of members of the community - first responders, parents, other students, etc. - literally wrap around the victims in a supportive embrace. The inner circle with the individual plaques is decorated with items left by visitors. Each of the names was covered in coins (which you can see in the gallery at the bottom of this post), and in one case, a dog tag left for a student who wanted to join the military. The number of the coins indicated that people often visit and leave their offerings – I suspect that many members of the community make regular visits here. The site is simple, but moving, and there was something about the coins that showed so much life in a place dedicated to the dead. A walking trail circles the memorial and leads to the top of the hill, from which position it is possible to look over the school’s running track and towards the school. On the far side is a small area of reflection where guests can look down on the totality of the memorial or away across a lake and towards the mountains. The power of the space is palpable, and I daresay that it is an appropriately beautiful place for this type of memorial. To that end, and I can’t stress this enough, is that Columbine High School is beautiful. Such is the memory I took away from the school. For all of the footage of the crying and suffering survivors, Columbine in real life is an idyllic place, which somehow makes the massacre so much worse and yet the recovery so much more inspiring. The high school is named after the Colorado blue columbine, the state flower, and the name is fitting. Columbine High School and Clement Park are clearly the flower of this community and you can feel a lot of love walking around the area. Recently, another scholar questioned me about the difference between memorialization and dark tourism, arguing that memorialization is not necessarily completed for the purpose of soliciting visitation and they aren't relatable concepts. I would agree that there are certainly differences needing qualification, as memorials are usually made to honor figures of importance, in this case the victims of a horrible crime, instead of appealing to travelers. But memorials often serve educational purposes as well, and to accomplish that task need to attract viewers. The connection between tourism and pilgrimage is a long-established conception within the social sciences, such that I do not hesitate to argue that tourists and pilgrims are often one and the same. Both tourists and pilgrims seek transformation in some form, often involving themselves in some sort of historical story. In this way, visiting the Columbine Memorial to learn about or remember what happened here is an act of pilgrimage, but one that also satisfies the curiosity of the dark tourist. Yes, gawkers and rubberneckers are frustrating, and Cullen documents that dark tourists descended upon Littleton in the wake of the shooting and continue to plague the town with inappropriate questions, but I suspect from my visit that most visitors are of the far more reflective type seeking to honor and engage more than dominate and violate. Furthermore, I reconfigure the work of art historian W.J.T. Mitchell, who famously questioned What Do Pictures Want? To Mitchell, artworks desire viewership to achieve their purpose. This post-modern anthropomorphizing of inanimate objects may be beyond where most people are willing to go in thinking about art, but serves the purpose of moving the interpretation of art away from the artist’s intention and towards the audience’s consumption of the artwork. In this case, whether memorials are intended for tourists or not, if audiences view them as places of pilgrimage and visitation they become tourist sites all the same. In this way, memorialization becomes transformation and meditation through dark tourism, and one does not preclude the other. Esteemed anthropology Sherry Ortner is famous for chronicling the pathways of anthropological thought throughout the past century. Recently, she argued that anthropology has taken a turn towards ‘dark anthropology’, which she describes as “anthropology that focuses on the harsh dimensions of social life (power, domination, inequality, and oppression), as well as on the subjective experience of these dimensions in the form of depression and hopelessness” (Ortner 2016: 47). Studies of dark tourism seem to fit this bill, as they revolve around places of death and tragedy. But I argue that the study of dark tourism are not dark in nature but actually quite optimistic. Dark tourism itself might be a misnomer for what actually occurs in these spaces, and the study of tourism at these sites may yet prove to be a way for anthropologists to see the light in the darkness. For my part, what I will remember most from my visit to Columbine is not the experience of standing on bloodstained ground, but instead the smiling, waving joggers who warmly greeted me on the walking trails and the students who respectfully stopped at the memorial on their way to other social activities. Much like how I often find inspiration in the strength of the Cambodian people, my Columbine experience was one of life – green grasses, blue skies, and new generations of people that remember the past but are not beholden to it. They are too busy building their present and their future to go backwards. Below is a collection of photographs of the Columbine Memorial that I share without comment (as my words can add nothing to what they represent). But I would finish this post by highlighting one of them, which summarizes so much about what anthropology can learn from dark tourist sites, and what you and I can learn by visiting places like these: ---

Cullen, Dave. 2016. Columbine. New York: Twelve Publishing. Kelly, Judith. 20 Apr 2019. "I Taught at Columbine. It is Time to Speak My Truth." Buzzfeed News. https://www.buzzfeednews.com/article/judithkelly/opinion-i-taught-at-columbine-it-is-time-to-speak-my-truth Ortner, Sherry. 2016. “Dark anthropology and its others.” Hau: Journal of Ethnographic Theory 6 (1), pp. 47-73. Mitchell, W.J.T. 2005. What Do Pictures Want?: The Lives and Loves of Images. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Sharpley, Richard and Philip R. Stone, eds. 2009. The Darker Side of Travel: The Theory and Practice of Dark Tourism. Bristol: Channel View Publications. Spencer, J. William and Glenn W. Muschert. 2009. “The Contested Meaning of the Crosses at Columbine” American Behavioral Scientist 52 (10), pp. 1371-1386. Strauss, Claudia. 2007. “Blaming for Columbine: Conceptions of Agency in the Contemporary United States.” Current Anthropology 48 (6), pp. 807-832.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorMatthew J. Trew Archives

April 2019

Categories

All

View Disclaimer and Terms of Use |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed